A few months ago no one would have anticipated that a small act of defiance in Tunisia would set in motion drastic changes to the political complexion of the Middle East. However, with the authoritarian regimes in Tunisia and Egypt having been ousted by their peoples, despots all over the region are wondering whether or not they are about to reap the whirlwind they have so thoroughly sown. While the regimes in Jordan, Yemen and Bahrain, being dependent upon western support, are trying to appease growing dissent, anti-western regimes in Iran, Syria and especially Libya, have no such qualms about using violence and intimidation.

A few months ago no one would have anticipated that a small act of defiance in Tunisia would set in motion drastic changes to the political complexion of the Middle East. However, with the authoritarian regimes in Tunisia and Egypt having been ousted by their peoples, despots all over the region are wondering whether or not they are about to reap the whirlwind they have so thoroughly sown. While the regimes in Jordan, Yemen and Bahrain, being dependent upon western support, are trying to appease growing dissent, anti-western regimes in Iran, Syria and especially Libya, have no such qualms about using violence and intimidation.

It is tempting to compare these events to what happened in the Communist world in the late 1980s. As the Soviets left Eastern Europe the people were allowed to create democratic nations, while in China any hopes for freedom were crushed by the Peoples’ Liberation Army during the massacre at Tiananmen Square.

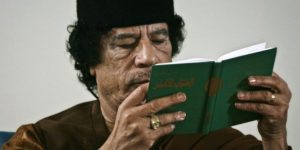

However, at least in the case of Libya, history may not repeat itself. While no one can say for sure whether or not the laughable Colonel Gadhafi will be overthrown there are signs to suggest he could be the next domino. Whether or not a post-Gadhafi Libya, let alone Egypt and Tunisia, will develop into legitimacy democracies, or lapse back into tyranny, is another matter.

Either way, it is likely that the Colonel’s days are numbered. The most effective means used by dictators to put down rebellions is violence. However, for violence to be effective dictators need the loyalty of the armed forces and the government, as well as the acquiescence of the majority of the population. To guarantee the former requires a shrewd combination of favours and punishments, while the latter is accomplished by fear and control.

Syria’s quashing of the Muslim Brotherhood in Hama during 1982, Saddam Hussein’s brutal crack down on the Shiites and Kurds after the Gulf War, and the Tiananmen Square massacre illustrate these points clearly. During these events there was no significant disobedience on the part of the governments or militaries, and the majority of the people stood on the sidelines. While some could argue that at least in Iraq the rebellion was popular, two factors should be kept in mind. Although it was popular among the Shiites and Kurds (who admittedly form a majority of the population), Saddam still had the loyalty of the Sunnis, who held the most powerful positions in the country, and were the most organized. Additionally, Saddam Hussein’s use of violence was particularly brutal and comprehensive compared to most government crackdowns.

It follows that dictators are usually overthrown by rebellions when they are unable to use violence in an effective manner to quash them. Obviously this is the case when a dictator cannot count on the loyalty of the government and the army, or the acquiescence of the people, to condone the necessary level of violence needed to quash a rebellion. This was seen in Iran during the late 70s, in Eastern Europe in 1989 after the Soviets had gone, and recently in Egypt where the military made it clear it would not attack the protesters.

With this in mind we should take a closer look at the current situation in Libya. While Gadhafi has not shied away from violence, it has not been used effectively enough to put down the rebellion. The reason is not because Gadhafi is unwilling to use brutal methods (far from it), but because he is increasingly losing the support of the government, the army, and the people.

Regarding the government, several ambassadors have already condemned his use of violence, the Justice Minister has resigned and the Oil Minister has fled the country. Even the Minister of the Interior, whose jobs should have been to crush the rebellion, has resigned. It is scary day for any dictator when his Minister of the Interior joins a rebellion.

The army has also proven to be lukewarm in its support for Gadhafi. So far two pilots and a naval vessel have defected to Malta, and a bomber crashed when its crew bailed out rather than bomb the protesters. Additionally the border guards at the Egyptian frontier have deserted and there are other reports of soldiers joining the protesters. More ominously, the military forces in Benghazi, Libya’s second city, have apparently abandoned the regime.

Perhaps most damning for Gadhafi is that the Libyan people are increasingly standing against him. According to many sources, the protesters now control Benghazi, and most of Eastern Libya. Meanwhile disturbances are spreading to cities in Western Libya and the streets of Tripoli are deserted except for thugs loyal to the regime. The Colonel cannot even play the religious card, as most of the country’s clerics have sided with the protesters.

So far, the momentum has favoured the protesters. Attrition is against Gadhafi as he has been continuously losing supporters and territory since the beginning of the rebellion. It seems that only one of two things could save him now: Either resorting to violence on the scale Saddam Hussein used in 1991 to crush the Shiites and Kurds, or outside intervention.

Both of these scenarios are extremely unlikely. The current state of the army precludes any realistic chance of the former. Any chance of outside help is even more remote. Egypt and Tunisia, Libya’s closest neighbours, are not going to help a tyrant after just having ousted their own. Syria and Iran, the countries most likely to sympathize with Libya, are too far away and weak to offer any meaningful help. The only countries that could offer any help to Gadhafi would be the United States and Britain, but while their relations with Libya have improved as of late, they have little reason, and even lesser will, to do so.

While it is not a foregone conclusion that Gadhafi will be overthrown, there is enough evidence to suggest that the odds are stacked heavily against him. However, if he does turn out to be the next domino, no one will be there to pick him up when he falls.