Maritime chokepoints are narrow stretches of water that connect two significant bodies of water. They are called chokepoints because they can easily be blocked due to their relatively constricted nature. Most maritime chokepoints are along major routes of international seaborne trade. Since 90% of the world’s trade is by sea the closures of such chokepoints usually have severe economic consequences for countries dependent upon such routes. For example, when the Suez Canal was closed from 1967-75 countries in East Africa and South Asia that relied heavily on the Canal for trade had to deal with significant increases in costs for shipping that resulted from the longer distances their ships had to travel by going around the Cape of Good Hope instead. Likewise, the closure of the Strait of Hormuz by Iran would likely result in widespread economic disaster as 40% of the world’s seaborne oil trade passes through it.

Maritime chokepoints are narrow stretches of water that connect two significant bodies of water. They are called chokepoints because they can easily be blocked due to their relatively constricted nature. Most maritime chokepoints are along major routes of international seaborne trade. Since 90% of the world’s trade is by sea the closures of such chokepoints usually have severe economic consequences for countries dependent upon such routes. For example, when the Suez Canal was closed from 1967-75 countries in East Africa and South Asia that relied heavily on the Canal for trade had to deal with significant increases in costs for shipping that resulted from the longer distances their ships had to travel by going around the Cape of Good Hope instead. Likewise, the closure of the Strait of Hormuz by Iran would likely result in widespread economic disaster as 40% of the world’s seaborne oil trade passes through it.

Perhaps more worrying is the fact that many routes of seaborne trade have several chokepoints spread out along their passage. As such the closure of any of these chokepoints can seriously disrupt seaborne trade to many of the nations concerned, especially those at either extremity of the route. For example countries in Northern Europe and the United Kingdom that trade with countries in the Indian Ocean usually prefer the shorter trade route that goes through the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. Unfortunately the closure of the Strait of Gibraltar, the Suez Canal, or the Bab el-Mandeb would force these nations to go around the Cape of Good Hope, open the blockade by force, or find other arrangements.

It is no coincidence that the British Empire had colonies or bases positioned along such routes. Look at any major trade route at sea and chances are you will find former British possessions dominating their chokepoints. Besides the obvious route through the Mediterranean to their crown jewel colony in India the British had the Falkland islands to watch the Drake Passage, their protectorates along the Persian Gulf to guard the Strait of Hormuz, the once powerful fortress at Singapore to safeguard the Strait of Malacca and its Cape Colony to patrol the Cape of Good Hope among others. Besides the former British Empire only the United States has the bases, and allies, to dominate the world’s major chokepoints.

The ability to control the world’s major sea routes has given these two countries distinct geopolitical advantages. Indeed, this ability is what made Britain historically, and America currently, both Superpowers. The control of these chokepoints with the combination of the Royal Navy at one time, and America’s Carrier fleets at the present, allowed Britain and now America to dominate world trade, project their military power on a global scale, and deny such capabilities to their enemies.

Since the 16th century the British have fought the Spanish, the Dutch, the French, and the Germans to control the seas, while America’s naval supremacy during the Cold War gave it a distinct advantage over the Communist bloc. While nations that dominate sea lanes gain an inestimable advantage in maritime trade and power projection, nations that relay on sea lanes but are unable to contest their dominance are extremely vulnerable. For example the naval blockade of Germany during the First World War, which was facilitated by Britain’s control of the English Channel and the GIUK (Greenland, Iceland, Unite Kingdom) Gap, was at least indirectly responsible for the deaths of a million German civilians. Also, American naval dominance during the latter stages of World War 2 provided an effective blockade of the Japanese home islands. Many military experts and historians believe that had the Americans not used nuclear weapons that Japan could have been starved into submission by the spring of 1946.

Controlling chokepoints and shipping lanes also allows countries to cut off reinforcements and supplies to enemy garrisons far away from friendly support. If these forces are unable to get help by non-naval means, they are vulnerable to being overrun by an enemy that can concentrate superior resources against them. This stratagem was used frequently by the British in its colonial struggles against Spain, France and Germany. For example, French possessions in North America and India were conquered, and Napoleon’s attempt to take over Egypt was frustrated, by the superiority of the Royal Navy and its possession of key chokepoints such as Gibraltar that kept the French Atlantic and Mediterranean fleets from combining into one force. Likewise the same chokepoints that allowed the Americans to blockade Japan with submarines automatically cut off isolated Japanese garrisons in the Pacific that were usually bypassed rather than eliminated.

Historically, attempts by inferior naval powers to seriously challenge dominant ones have been mostly ineffective. Typically, the best chance is for several leading naval powers to join forces and confront a common enemy who enjoys naval dominance. This was used effectively by the Spanish, Venetians and their allies to confront and defeat the Turkish fleet at Lepanto in 1571. It has also been used in the past by the French, Spanish and Dutch to fight the Royal Navy, albeit with limited success.

Trying to build a superior navy to defeat a dominant naval power has occasionally been attempted as well, notably by the French and Germans against the British and the Japanese against the Americans. This stratagem tends to fail for a number of reasons. For one thing the dominant naval powers usually have better, or at least more numerous, port facilities and superior ship production, not to mention more experience in fleet operations when it comes to actual fighting. Additionally, many nations that have tried to challenge dominant naval powers have had to balance their naval expenditures against maintaining standing armies. It is no coincidence that countries like Britain and America, which are not threatened on land, can easily build massive navies while continental powers like France and Germany have struggled historically to find a proper balance between their naval and land forces. Finally, at least in the case of France and Germany, British control of key chokepoints severely reduced the potential threat they posed to Britain.

For these reasons France and Germany failed to wrestle naval dominance from the British. Napoleon and Kaiser Wilhelm may have constructed impressive navies, but it is debatable what practical use they served as they were mostly impotent to challenge the Royal Navy. It is not unreasonable to suggest that they would have been wiser to invest more money in their land forces instead. Even if Napoleon had been able to create a superior fleet he would have had difficulty combining its Atlantic and Mediterranean elements due to Britain’s control of the Strait of Gibraltar, and even then it would not have necessarily guaranteed victory against the Royal Navy (it should be remembered that Sir Francis Drake’s victory against the Spanish Armada and Nelson’s triumph at Trafalgar were against numerically superior opponents).

Likewise, Britain’s control of the English Channel and the GIUK Gap would have at least allowed the Royal Navy to concentrate its strength against a theoretically stronger German fleet, and the indecisive nature of the naval battles between Britain and Germany during the First World War hardly provides assurance that the Germans would have been able to defeat Britain’s mastery of the seas.

The case of the Japanese challenging the Americans is different, at least theoretically, as Japan needed a powerful navy to guard its sea lanes and support its military expeditions across Asia. However, even had the Japanese completely destroyed the American Carrier fleet at Midway in 1942 the Americans were bound to overwhelm them eventually with their vastly superior ship production capabilities.

One notable case of an inferior naval power using a chokepoint to defeat a superior navy occurred during the Second Persian War when Persian forces invading Greece were dependent upon their navy to supply their advance. Themistocles, the Athenian Commander of the combined Greek navy, lured the Persian navy into the narrow waters of Salamis where it was unable to bring its superior numbers to bear, and scored a decisively victory against the Persians. After this defeat, Xerxes, the Persian king, retreated to Asia with most of his army.

Besides using direct methods to wrestle command of the seas from dominant naval powers, countries have used more limited means such as raiders and submarines in attempts to either starve them into submission, or at least weaken their maritime superiority.

Raiders have been used to capture, or destroy, merchant vessels or weaker warships. The British used raiders extensively against the Spanish in the 16th century while the Americans, the French and the Germans have used it against the British during the War of 1812, the Napoleonic Wars and even to a limited extent during both World Wars. Raiders can be easily dissuaded from operating around chokepoints, so long as these points are adequately patrolled. The use of raiders has decreased over time due to the establishment of convoys and advances in communications and propulsion that have allowed navies to track them more effectively (though ships plagued by piracy off Somalia’s coast and in the Indian Ocean may disagree).

A more dangerous threat to maritime powers has been the submarine. In both world wars the submarine proved its worth. Despite having few in numbers and being largely obsolete, German submarines during both wars came close to starving the British into submission. It was only the introduction of protected convoys in the First World War, and many improvements in submarine detection and effective air cover in World War 2 that saved Britain. It is not surprisingly that Winston Churchill, who himself had held the position of First Lord of the Admiralty twice once said “the only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.”

However, it is probable that the allies made more use of submarines than the Germans. The British used them so effectively against Italy that Rommel was often robbed of necessary supplies to effectively fight the 8th Army in North Africa. The Americans enjoyed even more success against the Japanese, more or less cutting Japan off from its Empire and bringing it to the brink of starvation. This is an impressive achievement considering submarines accounted for perhaps 2% of the American navy.

Unfortunately, for dominant maritime powers, chokepoints are not as effective against submarines as they are against raiders. While in theory it should be easier to detect a submarine travelling through a chokepoint than at open sea, it is just a case of finding a needle in a smaller haystack. While it is certainly risky for submarines to pass through chokepoints even the Germans managed to get 40 U-Boats through the Strait of Gibraltar (arguably one of the narrowest chokepoints) in World War 2, though 10 more were damaged and 9 more were sunk when attempting to do so. Likewise, while the blockade of the Strait of Otranto during World War 1 cut off the Austro-Hungarian Empire from seaborne trade outside the Adriatic, it did little to prevent submarines from coming and going through the strait.

However, it has always been the case that the most effective means of combating submarines has been convoys and early detection methods rather than trying to hunt them down.

While there are many maritime chokepoints there are a few in particular that hold significant strategic or economic value. While it is difficult to establish their relative importance the most notable chokepoints for seaborne trade would include the Strait of Hormuz, the Suez Canal, the Panama Canal, the Strait of Malacca, the Bab el-Mandeb, the Dardanelles and Bosporus straits, the Strait of Gibraltar, the English Channel, and the Danish Straits.

As stated earlier, approximately 40% of the world’s seaborne oil trade passes through the Strait of Hormuz. The Strait of Hormuz separates the Persian Gulf from the Indian Ocean. As something like 50% of the world’s proven oil reserves are in countries that rely on passage of the strait to export their oil its closure would be devastating to the global economy. Iran could potential blockade the strait in retaliation if the Americans, or the Israelis, bombed its nuclear facilities. However, despite threatening to close the strait from time to time the Iranians would be foolish to do so as they are heavily reliant upon their own oil exports for revenue. Even if they did the blockade would not last long as American Carrier fleets would quickly arrive and defeat the Iranian forces as they did in a similar occasion in 1988 during the Iran-Iraq War.

The Suez Canal allows trade through the Eastern Mediterranean and the Red Sea. It was made during the late 19th Century to create a shorter sea route from Europe to the Far East than having to go around the Cape of Good Hope. Its strategic importance for the Europeans was demonstrated when the British and French were willing to go to war with Egypt over it in 1956 to reclaim its ownership. The blocking of the Canal in 1956 and 1967-75 had significant economic repercussions for those countries largely dependent upon it for trade. Even today roughly 7.5% of the world’s seaborne trade flows through the Canal.

The Panama Canal was built to shorten sea communications between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. It is generally a shorter, and less dangerous, route than the Drake Passage for most countries trading between these areas. It is not a significant trade junction for oil, as many oil tankers cannot fit through its locks. However it is still a major hub for world trade as more than 14,000 ships pass through it annually. Like the Suez Canal, the Panama Canal has seen conflict. Japan had some incredible schemes they never enacted to attack the Canal during the Second World War. Additionally securing the Canal Zone was an important consideration during America’s invasion of Panama in 1989.

The Strait of Malacca is the main passage between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific. It is a vital junction as 25% of the world’s traded goods pass through it. Countries like China, Japan and South Korea are especially dependent upon this route for their oil as ¼ of the world’s oil trade traverses it as well. This is undoubtedly one of the reasons why China is anxious to build a blue-water navy; to secure its maritime communications. If the Strait were to be closed the two closest alternate passageways (the Sunda Strait and the Lombok Strait) would be poor substitutes due to the former’s narrow and shallow nature and the latter’s remote location. The British considered the Strait of Malacca so important that it built a powerful fortress at Singapore before the Second World War to guard it against naval attack. Unfortunately for the British, the Japanese attacked it overland via the Malay Peninsula in 1942 and captured it with ease.

The Bab el-Mandeb connects the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean. Blocking its channel would render the Suez Canal mostly redundant, as free passage of both chokepoints is necessary to navigate the shorter sea lanes between Europe and Asia via the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean, thereby bypassing the much longer route via the Cape of Good Hope. The Egyptians blockaded the strait during the Yom Kippur War of 1973 which could have been devastating to the Israelis had it continued, as they were depended on it for their oil imports from Iran. The strait is also in a region rife with modern piracy, which remains mostly unchecked despite countless warships from many nations patrolling the area.

The Dardanelles and the Bosporus Straits dominate access between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. This gives Turkey considerable political leverage as it controls both straits. Together they form a significant oil chokepoint as it is Russia’s (as well as other regional nations with large amounts of oil) primary route for exporting its oil goods. On average 50,000 ships, including 5,500 oil tankers, pass through them every year. Besides their economic importance the straits have held much strategic value throughout history. When the Persian King Xerxes invaded Greece in 480 BC he built a bridge across the Dardanelles to reach Europe. Unfortunately, it was destroyed by a storm and he ordered his minions to punish the sea with 300 lashes. Russia has tried for centuries to control the straits to gain access to the Mediterranean and this ambition did much to provoke the Crimean War. Yet perhaps the most well known historical instance was the failed attempt by the British to conquer the straits during the First World War in order to knock Turkey out of the conflict.

The Strait of Gibraltar separates the Atlantic Ocean from the Mediterranean. As previously noted, it is one of the primary chokepoints along the vast trading route from Northern Europe to the Indian Ocean. Historically, it has been a strategic gem for the British (also previously noted) as it has allowed them to control the Western Mediterranean and helped them prevent the French Atlantic and Mediterranean fleets from combining.

The English Channel is the shortest route for seaborne trade to the rest of the world for the Low Countries, Northern Europe, and nations connected to the Baltic Sea. The alternate route through the GIUK Gap is much harder to block, but significantly longer. The English Channel is the world’s busiest seaway with 500 ships passing through it each day (which amounts to approximately 180,000 a year). The vast majority of oil imports for these nations either pass through the Channel or come from Russia via the Baltic Sea. The Channel has a colourful history with the Norman Invasion in 1066, the Anglo-Dutch Wars, the Spanish Armada, the Battle of Britain and the D-Day landings among countless other incidents.

The Danish Straits allow access between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea. All seaborne trade leaving the Baltic must pass through them or the Kiel Canal (the busiest artificial sea lane in the world with 43,000 ships traversing it annually). Besides being the key junctions for Baltic trade the Danish Straits serve as a significant oil chokepoint, with more than 3,000,000 barrels (mostly from Russia) of oil passing through it each day. The straits were the scene of two actions by the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars. In the first instance Nelson led a successful attack in 1801 against the Danish fleet while in the second instance the Royal Navy bombarded Copenhagen to force the Danes to surrender their fleet (which the British believed was at risk of falling into Napoleon’s hands). The British also seriously undermined the Russian economy during the Crimean War by blockading the straits.

A few other chokepoints are not as important to global trade, but still hold significant strategic value.

The Taiwan Strait separates China from Taiwan. Japan often claims this passage is vital for its trade, especially regarding its oil imports from the Middle East, but this is disingenuous because the waters east of Taiwan actually provide a shorter route. In reality the Chinese gain the most by controlling the straits, though not for economic reasons. A simple look at any world map shows that Taiwan is strategically placed to block China’s naval dominance of the Pacific. As long as Taiwan is an ally of the United States, or at least retains independence from China, it provides an effective base to blockade the Chinese coast in the event of war. This is another reason the Chinese are building a modern fleet; to challenge America’s dominance of the Pacific Ocean.

The Korea Strait separates the Sea of Japan from the East China Sea. It holds much economic value to South Korea and Japan. It has also historically facilitated Japanese dominance of the Sea of Japan. A Mongolian fleet trying to invade Japan in the 13th Century was destroyed by a massive typhoon. Japan’s control of the strait gave it a significant advantage during the Russo-Japanese War in the early 20th Century, allowing it to prevent the Russian fleet at Vladivostok from combining with its sister fleet at Port Arthur. It was also the scene of the naval Battle of Tsushima where the Japanese Navy fought the Russian Baltic fleet sent across the world only to be sunk after one day’s fighting. Control of the strait also allowed the American occupational forces in Japan to supply the Pusan perimeter in Korea during the early days of the Korean War, buying enough time for General MacArthur to launch a daring amphibious assault at Inchon that turned the tide of the conflict.

The strait of Tiran allows Israel and Jordan to engage in maritime trade via the Red Sea. While it is of little importance when it comes to world trade its closure could potentially lead to severe economic dislocation. Egypt has the ability to blockade the Strait due to their control of Sharm el-Sheikh. Blocking Israel’s trade route through the strait from 1949-56 and again in 1967 were significant factors that led to the Suez Crisis and the Six Day War, both of which had severe economic repercussions far beyond the tiny strait. The strait’s strategic importance to the Israelis was deemed so important that Moshe Dayan, arguably Israel’s most famous general, once said that it was better to “have Sharm el-Sheikh without peace, than peace without Sharm el-Sheikh.” However, Israeli control of Sharm el-Sheikh after the Six Day War did not help them during the Yom Kippur War when the Egyptians were able to cut off Israel’s trade through the Red Sea by blockading the Bab el-Mandeb (once again showing how different chokepoints often affect each other).

Maritime chokepoints separate two significant bodies of water and often serve as vital strategic and trade junctions. Most major sea routes contain several chokepoints, the closure of any resulting in severe economic dislocation for the countries concerned. Superpowers like the former British Empire and America have used major maritime choke points, in conjunction with superior naval power, to dominate world trade, project their military might abroad, and deny such capabilities to their enemies. Secondary naval powers have tried to challenge naval superpowers by combining their naval forces with other countries, attempting to build superior fleets, and using raiders and submarines to capture, or destroy, inferior warships and merchant shipping. These means usually fail due to the vast resources naval superpowers control due to their domination of the world’s seaborne trade.

Chokepoints such as the Strait of Hormuz, the Suez Canal, the Panama Canal, the Strait of Malacca, the Bab el-Mandeb, the Dardanelles and Bosporus straits, the Strait of Gibraltar, the English Channel, and the Danish Straits are perhaps the most important junctions for world trade (and for seaborne oil commerce). Other such chokepoints like the Taiwan Strait, the Korea Strait, and the Strait of Tiran are not as important to trade, but are potential flashpoints for conflict that could result in severe economic fallout for global markets. As long as trade is predominantly done by sea the control of the planet’s key maritime chokepoints guarantees control of the world.

Bibliography

Bennett, Geoffrey. Naval Battles of the First World War. London: Penguin Books, 2001.

Corbett, Julian. Principles of Maritime Strategy. New York: Dover Publications, 2004.

Fahey, John. Atlas of the Middle East. Washington D.C: National Geographic, 2003.

Lewis, Jon. The Mammoth Book of Battles. London: Robinson Publishing, 2000.

Mahan, Alfred. The Influence of Sea Power upon history: 1660-1783. New York: Dover Publications, 1987.

Nalty, Bernard. The Pacific War. London: Salamander Books, 1999.

Scribd Article on Chokepoints [Online]http://www.scribd.com/doc/47660084/choke-points [2011, March]

Website on World Oil Transit Chokepoints [Online]http://www.eia.doe.gov/cabs/world_oil_transit_chokepoints/panama_canal.html [2011, March]

Wikipedia Article on Royal Navy’s Chokepoints [Online]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Choke_point#Royal_Navy_choke_points [2011, March]

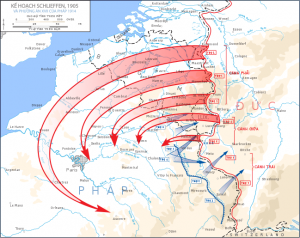

The “Schlieffen Plan” of the First World War is arguably the most widely known battle plan in the history of warfare. It is thought that Count Schlieffen’s plan was based on Hannibal’s victory at Cannae and inspired by the last chapter from Carl Von Clausewitz’s “On War” entitled “The Plan of a War designed to Lead to the Total Defeat of the Enemy.” Ultimately the plan failed. Or did it? It is well known that certain aspects of the plan were changed by Schlieffen’s successor Moltke the Younger. Many of these changes were crucial to the original plan and Count Schlieffen criticized Moltke the Younger for altering his magnum opus before he died.

The “Schlieffen Plan” of the First World War is arguably the most widely known battle plan in the history of warfare. It is thought that Count Schlieffen’s plan was based on Hannibal’s victory at Cannae and inspired by the last chapter from Carl Von Clausewitz’s “On War” entitled “The Plan of a War designed to Lead to the Total Defeat of the Enemy.” Ultimately the plan failed. Or did it? It is well known that certain aspects of the plan were changed by Schlieffen’s successor Moltke the Younger. Many of these changes were crucial to the original plan and Count Schlieffen criticized Moltke the Younger for altering his magnum opus before he died.