Cannae holds an unique place in military history and theory. It was arguably the most brilliant tactical victory of all time. It was also among the few cases where a significantly outnumbered opponent not only defeated, but completely annihilated, the opposing army. It was so successful that more than 2000 years later soldiers still dream about using a double encirclement to inflict an overwhelming defeat upon an enemy in battle. However, despite the undoubted tactical success Hannibal achieved against Rome at Cannae many of these same soldiers seem to have ignored other less savory lessons from the battle. Indeed Hannibal’s victory at Cannae did not lead to decisive strategic results and ultimately Carthage lost the war. Cannae’s tactical results have tended to overshadow the fact that strategically it accomplished nothing significant for Carthage in the long term.

Cannae holds an unique place in military history and theory. It was arguably the most brilliant tactical victory of all time. It was also among the few cases where a significantly outnumbered opponent not only defeated, but completely annihilated, the opposing army. It was so successful that more than 2000 years later soldiers still dream about using a double encirclement to inflict an overwhelming defeat upon an enemy in battle. However, despite the undoubted tactical success Hannibal achieved against Rome at Cannae many of these same soldiers seem to have ignored other less savory lessons from the battle. Indeed Hannibal’s victory at Cannae did not lead to decisive strategic results and ultimately Carthage lost the war. Cannae’s tactical results have tended to overshadow the fact that strategically it accomplished nothing significant for Carthage in the long term.

The “Battle of Cannae” was a pivotal moment during the “Second Punic War” fought between Carthage and the Roman Empire to determine which power would dominate the Central and Western Mediterranean. This conflict was waged a generation after the “First Punic War” where Rome had ultimately triumphed over the Carthaginians. During this earlier conflict the Romans, despite being predominantly a land power, had built up a significant navy and eventually defeated the Carthaginians, who had been the major naval power in the Central and Western Mediterranean. This resulted not only in the Romans becoming the major naval power in the region, but also in the Romans annexing Carthaginian territory in Sicily, and later Sardinia and Corsica, and nearly reducing Carthage to a second rate power. While the Romans basked in the glory of their new power and expansion, the Carthaginians yearned for revenge and decided to seek expansion in Spain where Roman naval power could not impede them.

The main Carthaginian General in Spain was a man named Hamilcar Barca who was, arguably, Carthage’s most skilled commander and one of the few Carthaginian leaders not defeated by the Romans during the “First Punic War.” Hamilcar and his soldiers effectively annexed most of Spain for the Carthaginian Empire and raised and trained an army that would later inflict many impressive defeats upon Roman forces during the next war between the two states. After he died, power in Spain rested first with his son-in-law Hasdrubal, and later with his son Hannibal, who would be both the instigator, and dominant personality, of the “Second Punic War.”

While much of what has been written about Hannibal is suspect due to obviously biased sources and the sheer passage of time, there is no doubt that he was a brilliant general; capable of impressive maneuvers, possessing considerable foresight, and instilling respect from friends and foes alike. He belongs in the same category as Robert E. Lee and Erwin Rommel, two other commanders who were generally more tactically astute than their opposite numbers, but who were doomed to lose due to their nations’ inferior resources and corrupt political systems. Just like Robert E. Lee and Erwin Rommel, Hannibal produced the most impressive tactical victories during his respective war and is generally more popular in military history than his opponents who actually won in the end.

The catalyst for the “Second Punic War” occurred at Saguntum, a city allied to Rome south of the Ebro River in Spain. While the Romans accepted Carthage’s dominant position in Spain they had somewhat brusquely limited Carthaginian expansion to south of the Ebro River. This, along with the previous opportunistic Roman annexations of Carthaginian territory in Sardinia and Corsica while Carthage was preoccupied during the “Mercenary War,” provoked considerable anger and indignation in Carthage. The final insult to Carthage occurred when the Romans became allies with Saguntum, a city well below the Ebro and obviously within Carthage’s sphere of influence. From the Carthaginian point of view such a move was insulting and seemed as though Rome viewed them as a second rate power.

In 219 B.C, Hannibal, having seized control of the Carthaginian army in Spain after the assassination of Hasdrubal in 221 B.C, sacked Saguntum after a lengthy siege in open defiance of Rome. Initially, the Romans, in an attempt to prevent war, requested that the Carthaginians condemn the behavior of Hannibal and to turn him and his senior officers over to their custody. When Carthage refused to do so Rome declared war and the “Second Punic War” began.

Whether or not Hannibal attacked Saguntum to provoke war with Rome is questionable, but what is not debatable is that he was well prepared to attack Rome once hostilities commenced. As Roman naval power was more than double of Carthage’s (roughly 220 quinqueremes to Carthage’s 105) there was little chance of landing troops in Italy via ships with a reasonable degree of success. As such, Carthage could either march most of its forces through Spain, Southern France, and then Italy to attempt to defeat Rome on its own territory, or stay on the defense and try to wear Roman forces down and bring them to the negotiation table. In the case of invading Roman territory the Carthaginian forces would have many handicaps including having to march long distances over unforgiving terrain inhabited by often unfriendly inhabitants, as well as the fact that the Romans would have a significant advantage in manpower and resources once they got to Italy. While this would seem to suggest that it would have been wiser for Carthage to adopt a more defensive strategy there are two good reasons they did not.

Firstly, during the “First Punic War” the Romans waged an extremely aggressive war. Even though the war was technically a limited conflict, as it was predominantly over the control of Sicily, the Romans treated it as what would be called, in the 20th Century, a “total war” and mobilized massive forces and sought decisive battles to impose its will upon Carthage. This was in contrast to the Carthaginian conduct during the war which was more cautious and limited as they merely sought to gain advantages to ultimately negotiate from a position of strength. In the end, Roman resources, persistence and boldness prevailed and the Carthaginians realized that in any future conflict that the Romans would either fight until they won or were put in a position they could no longer continue to wage war.

Secondly, Hannibal, the de-facto instigator of the war, was an offensive minded soldier, and preferred risk, decision, and initiative to caution, attrition and waiting. Like all great captains from Alexander to Napoleon he preferred going for total victory, however risky, instead of taking solace in the advantages of the defense.

On paper the odds were heavily stacked in Rome’s favor. Rome had more manpower, more military and naval power, more economic strength, and better political cohesion. Much of this had to do with the respective political systems in Rome and Carthage. The Roman republic, though far from what would today be called a “liberal democracy,” allowed its citizens considerable freedom and the right to choose their leaders. Even more, it usually allowed defeated powers the same rights as Romans and thus often turned conquered subjects into loyal, and productive, citizens. In contrast Carthage was a more authoritarian state and non-Carthaginians were either treated as slaves or second class citizens. The end result being that while Carthage viewed much of its population with suspicion and often had to resort to using mercenary soldiers of variable quality, the Romans had a seemingly inexhaustible reserve of manpower from a generally loyal population base. According to Polybius, the Romans had the potential manpower of 700,000 infantry and 70,000 Cavalry on the eve of war, numbers which the Carthaginians theoretically had little chance of beating in a prolonged war of attrition.

This, in fact, figured into Hannibal’s calculations. With insufficient naval power to land enough troops directly into Italy, faced with the likely prospect of losing a considerable portion of his forces passing both the Pyrenees and Alps to reach Italy, and confronting numerically superior forces given the Roman system of governance Hannibal adopted a very deliberate strategy. He aimed to gain quick and decisive victories over Roman forces to gain favor among Roman enemies such as the Gauls as well as motivating Roman allies to desert in favor of Carthage. The idea being that if he could convince Rome’s enemies and allies that Carthage could beat the Romans in battle that they would join his cause and change the balance of power between Rome and Carthage enough to either defeat Rome outright or enable him to negotiate peace from a position of strength. After Cannae, he arguably came close to doing so.

Hannibal and his army left New Carthage in Spain in the late spring of 218 B.C. and had to cross mountain chains, treacherous rivers, and hundreds of miles of territory filled with generally hostile inhabitants. Of the nearly 100,000 soldiers he left with less than 30,000 successfully crossed the Alps. While Hannibal was focusing on Italy, the Romans decided to send one army to Spain to fight Carthaginian interests there and another one to Sicily to prepare for the invasion of Carthage. This left them relatively weak in Northern Italy when Hannibal appeared in late 218 B.C. While, with hindsight it is easy to censure Rome for its clumsy attempts to stop Hannibal from 218-216 B.C. it is fair to point out that given the incredible distances and horrible attrition Hannibal’s forces suffered from the march from Spain to Italy it is perhaps easy to see why the Romans considered such a strategy as both unlikely and desperate.

Yet unlikely or not, Hannibal’s forces crossed the Alps and soon met a strong Roman army near the Trebia River in December 218 B.C. The “Battle of Trebia” was similar to the “Battle of Cannae” in many ways. The Romans were superior in infantry while Carthage was superior in cavalry, utilized the terrain to their utmost advantage, and had roughly 30 elephants. Hannibal also placed a small force of 2000 infantry and cavalry in broken terrain to the left flank of where he anticipated the Roman line would be once its army crossed the Trebia River. The Romans had close to 38,000 infantry, heavy and light, while the Carthaginians had 28,000. Likewise, the Romans had 4000 cavalry while the Carthaginians had 10,000, evenly distributed along both flanks of their army.

Despite having numerical superiority the Romans were helplessly outclassed at Trebia. Hannibal’s cavalry were both superior in numbers and quality than the Roman’s, his elephants produced a disproportionate psychological effort on the enemy, and the Romans had their backs to the river. The Romans were also tired, hungry and cold (having to cross the Trebia River in icy conditions) as they spent most of the day deploying on the West Bank of the Trebia while Hannibal wisely used his light cavalry and light infantry to delay the Romans and allowed his infantry to rest as long as possible before being deployed on the field of battle.

The battle itself does not take long to describe; the Carthaginian cavalry on both flanks quickly quashed the Roman and allied calvary at which point Hannibal’s Numidian horses turned to harass the flanks of the Roman infantry while his Iberian and Gaulish horses pursued the defeated Roman and allied cavalry. Meanwhile the Carthaginian light infantry and elephants joined in the attack on the Roman centre and the 2000 Carthaginians hiding behind the Roman lines rushed to attack the Roman centre from behind; effectively encircling the Roman army. The only setback to Hannibal’s plan was when 10,000 heavy Roman infantry managed to break through the numerically inferior Carthaginian infantry in the centre and escaped the battlefield in good order. However, this was a minor inconvenience for Hannibal as the Carthaginians managed to kill or capture the lion-share of the nearly 45,000 Roman soldiers and allies at Trebia.

After his unequivocal victory at Trebia Hannibal rested his forces. Unfortunately for him many of his soldiers, and all but a few of his elephants, died in the cold conditions after the battle. However, he soon marched south again, ravaging the countryside to provoke the Romans into battle and trying to recruit Gauls in the area and convince Roman allies to desert by showing Roman impotence by their failure to stop his advance. At the same time the Romans, who were not unduly shaken by their defeat at Trebia, raised another two consular armies to find and destroy Hannibal’s force. The Romans once again elected two consuls for the coming year and the one who would next face Hannibal in battle was Gaius Flaminius.

According to ancient sources Flaminius was a rash and aggressive man who recklessly sought the quick annihilation of the Carthaginian army in Italy as soon as possible, whatever the conditions. Whether or not this is a fair appraisal is questionable as many of the sources of this period were biased, or owed patronage to Roman families who wanted to denigrate their rivals. However, the actual outcome of the next battle between Hannibal and Rome showed that Flaminius was anything but cautious or thorough. But to be fair to Flaminius his predecessors were no less circumspect or unlucky when they charged in blindly to attack Hannibal at Tacinus and later Trebia in 218 B.C. Indeed, Roman commanders and soldiers were by nature bold and aggressive and Flaminius can arguably be considered as a scapegoat for what was at the time a Roman military system that was very slow to adapt to Hannibal’s methods.

As Hannibal marched down the Italian peninsula he was pursued closely by Flaminius, who was eager, and no doubt pressured by Roman public opinion, to bring the Carthaginian commander to battle as soon as possible. The site of the battle between these two antagonists would be on the northern shore of Lake Trasimene. Hannibal had scouted the area and found a perfect area to trap and destroy the pursuing Roman army. The path along the northern shore was generally narrow and dominated by hilly terrain overlooking the lake. The geography was such that it would be easy to seal off the entrance, and exit, of the path near the shoreline, as well as hiding an army in the heights above.

Hannibal’s plan was to march through the pathway during the day, and then double back at night and occupy the high ground before the Roman army arrived the next day. He placed his Spanish and Libyan veterans on the ridge dominating the far exit of the pass where the Romans could see them once they entered the passage (thus trying to lure them into battle). He also placed his Gauls and light troops in the centre to fall on the Roman army once it had advanced sufficiently into the trap, while his cavalry were placed at the rear, ready to cut off the Roman escape route.

At dawn on June 21st, 217 B.C, despite the fact it was misty, and without bothering to send out a reconnaissance force to scout ahead, Flaminius ordered the Roman army to march through the pass. Advancing through the passage his lead troops eventually saw the Spanish and Libyan soldiers holding the ridge commanding the exit of the route and Flaminius ordered his soldiers, still in marching formation, to prepare for battle. However Hannibal’s forces soon descended the hills and fell upon the Roman ranks, who were still generally not formed up to fight, and who were now trapped between the entrance and exit of the pass. The Carthaginians attacked from high ground, and the Romans had the lake to their backs. Under these circumstances; surrounded, in poor fighting formations, and up against Hannibal’s elite forces, there is little doubt that the Roman army was doomed to an unpleasant fate.

In fact the battle was a comprehensive victory for Hannibal who killed or captured all but 6000 Roman soldiers who had been part of the vanguard and managed to escape. However, even this small consolation for Rome was lost when Hannibal’s forces found, surrounded and captured this force the next day. For the price of perhaps 1500-2500 casualties Hannibal had more or less crushed a Roman army and inflicted between 25,000-30000 casualties. The genius of Trasimene was perhaps best described by Robert O’Connell as “the biggest ambush in history, the only time an entire large army was effectively swallowed and destroyed by such a maneuver.”

If this were not enough, Rome suffered a further disaster when the cavalry from the other Roman army in Italy, which had not yet learned of the defeat at Lake Trasimene, was sent to make contact with Flaminius’s force. The cavalry, like Flaminius’s army before it, was ambushed and destroyed by Hannibal’s forces. With one army left and devoid of calvary the Roman republic’s chances of victory against the Carthaginians suddenly appeared slim indeed.

After Rome’s defeats at Ticinus, Trebia, Trasimene, and the recent loss of its cavalry, the Roman people finally sobered up to the possibility that Hannibal represented a mortal threat to the Republic. In the near panic, after these setbacks, the Roman senate appointed a dictator to coordinate Rome’s response to Hannibal. Usually the Roman republic was mainly run by two consuls (as the Romans were afraid of giving any man too much power), and the Senate, along with some collaboration with the Tribunes and the masses. However, in emergencies, much like modern day war measures acts in liberal democracies, the Roman republic often resorted to appointing dictators for 6 month terms to quickly and decisively accomplish what needed to be done. Dispensing with long winded debate, and eschewing yellow tape and petty procedures, the Romans generally entrusted the title of dictator to a man of known ability, and integrity, to use all means necessary to save Rome from whatever impending disaster confronted it. In the summer of 217 B.C. the Romans chose Quintus Fabius Maximus to be the savior of Rome. In the event, he was an unorthodox, but fortunate, choice.

He had an impressive enough resumé; having served in the “First Punic War” and having also held the Consulship twice. However, he was also old for a Roman general, at 58, and was not generally popular before, or during, his dictatorship. Either way Fabius Maximus wisely adopted cautious strategy and tactics against Hannibal and ultimately allowed Rome to not only recover from her potentially fatal position in the summer of 217 B.C, but to face Hannibal with considerable, though with hindsight perhaps foolish confidence, the next summer.

Realizing that Hannibal’s strategy involved bringing Roman armies to battle as quickly as possible (and on the ground of his choosing) to destroy them, Fabius Maximus generally avoided battle, stuck to strong positions and high ground, and only engaged Hannibal’s forces in smaller skirmishes whenever the Romans held the advantage. Aware that Hannibal’s weaknesses were his lack of food, supplies and a secure base, Fabius Maximus destroyed, or removed food stocks, along Hannibal’s route, attacked his foragers, sought to wear down his forces via skirmishes and small scale ambushes, etc. Fabius’s objective was simple; either starve Hannibal enough to force him to abandon his campaign in Italy, or give Rome time to amass enough forces to confront Hannibal in battle with sufficient numerical superiority to offer a reasonable chance of victory.

Such a strategy; slow, defensive and attritional, was, and has generally been, unpopular in military history from Darius II’s refusal to enact it during Alexander the Great’s invasion of the Persian Empire to the Russian’s equivocation during Napoleon’s invasion in 1812. It is not surprisingly that the Romans, being by nature aggressive, offensive minded, and straightforward in their military methods, despised Fabius’s cautious methods. Ultimately, the Romans rewarded Fabius’s efforts with the nickname the “Cunctator” or the “Delayer,” an obvious insult given the inherently bold nature of Roman society. While it is hard to blame the Romans for their displeasure as the Carthaginians burned, looted, and moved across the Italian peninsula with apparent impunity, there is no doubt that Fabius’s strategy was the best option at the time as the Romans could not face Hannibal in open battle with a likely degree of success.

An incident during this time confirms this. Fabius’s second in command, Marcus Municius Rufus, whom he often had a strained relationship with, and who generally urged a more aggressive stance against Hannibal, managed to win a significant skirmish against Hannibal’s forces near Gerunium. The Roman people, not surprising given their displeasure at Fabius’s methods, took the unprecedented step of voting Marcus equal powers as Fabius. Thereupon Marcus openly sought battle with Hannibal with his forces while Fabius continued on the defense with his own. Soon Marcus clashed with Hannibal’s forces and was only rescued by the timely intervention of Fabius’s troops, after which Marcus relinquished ultimate power to Fabius once again. By this time the Romans generally realized the wisdom of Fabius’s policies and the next great clash between the Romans and Carthaginians would not occur until Cannae in 216 B.C.

In the end Fabius’s strategy did not force Hannibal to withdraw from Italy or seriously impact his army’s capabilities. However, it did allow the Romans and their allies the breathing room, from the summer of 217-216 B.C, to amass what was at that time the strongest army ever raised by the republic. Having considerable numerical superiority over Hannibal’s army, and moving against what was hoped to be an increasingly starved and isolated Carthaginian force in Southern Italy, the Romans had more reason to be confident of winning since Hannibal had passed through the Alps two years earlier.

After Fabius’s term of dictator was over the Roman people elected two new consuls; both of whom promised to quit the vacillation of the war effort and bring Hannibal’s army to battle and defeat it. This was understandable as even though Fabius’s tactics had saved Rome from early defeat Roman society, naturally impatient and aggressive, found them weak and indecisive. Yet without the benefit of hindsight, it is hard to judge that the Romans, having survived long enough to amass a clearly superior army, on paper at least, to Hannibal’s, voted to end the rape and pillage his forces were inflicting in Italy.

Given the sheer size of the Roman and allied army amassed this force was clearly meant to find and destroy the Carthaginian army in Italy; a much smaller force would have sufficed to harass, or observe, Hannibal. Once again, without hindsight, the Romans had many reasons to adopt an aggressive strategy in 216 B.C. Their resources, given the time to accumulate after Fabius’s cautious strategy, allowed them to field a significantly numerical superior army to Hannibal’s. Meanwhile, Hannibal, despite winning over much of the Gauls, had still failed to convince Rome’s many allies in the Italian peninsula to desert her. Finally, while not yet at a critical point for supplies or recruits, Hannibal and his forces were intruders in a hostile country, without a secure base of operations or the means to consistently support their needs. Indeed Hannibal’s forces maintained their long and seemingly confusing march since arriving in Italy because they had to keep moving to pillage food and supplies in order to continue operating.

Thus, from a strategic point of view, the Roman objective of 216 B.C. cannot be faulted. Hannibal’s army was the Carthaginian centre of gravity in the war and its destruction would both secure Italy and allow the Romans to take the fight to the Carthaginian homeland as well as their possessions in Spain. Hannibal’s army in Italy was relatively isolated and suffering from supply woes while the Romans could amass a superior army. Finally, the political pressure from allies and Roman citizens upset from Carthaginian excesses on Roman soil could not be easily ignored. The Roman defeat of Hannibal’s army in Italy offered the best strategic results for Rome in the war. Unfortunately for Rome, when the great contest of arms occurred at Cannae it seriously underestimated the tactical sophistication of Hannibal and his army.

The campaign in 216 B.C. from the election of the Roman consuls to the “Battle of Cannae” was not nearly as momentous, or descriptive, as Hannibal’s campaigns in Italy in late 218 or 217 B.C. Suffice it to say once Rome’s policy changed from attrition to decision after the end of Fabius’s term as dictator the Roman army pursued the Carthaginian army until it found a reasonable time and place to engage it. That place was just outside Cannae.

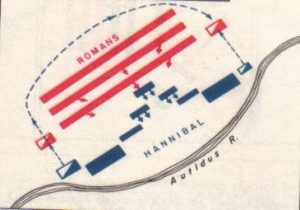

The Roman and allied army at Cannae was massive, with perhaps 86,000 infantry, calvary, and garrison troops. Hannibal’s army was significantly smaller, with arguably 50,000 in all. The Romans enjoyed a clear numerical superiority, especially in infantry. However, the Roman and allied cavalry were numerically weaker than Hannibal’s heavy and light cavalry, at approximately 6000 to 10000 respectfully. Additionally, Hannibal’s cavalry were also better trained and motivated than their Roman opponents who they had consistently beaten in battle since the beginning of the war. As for the infantry balance while Rome’s scores of heavy legions were generally better equipped than their Carthaginian counterparts, Hannibal’s 8-10,000 Libyan soldiers at Cannae were the best infantry on the field. Perhaps more important was how each side deployed their soldiers on the battlefield. As will be seen, Hannibal deployed his forces in the most efficient means possible whereas the Romans used their numerical superiority in a wasteful fashion.

The terrain at Cannae favored Hannibal’s army. Varro, the Roman consul who was in charge of the army during the battle, chose to deploy in the area because he thought the hills near Cannae on one flank, and the Aufidius River on the other, would offer his outnumbered and outclassed Cavalry a chance to hold their ground as the infantry battle would be decided. Without hindsight this was not unreasonable; at Trebia the Roman centre had burst through the Carthaginian centre and even at Lake Trasimene the Roman vanguard had punched through the trap and initially escaped. In both of these battles the Roman cavalry had been either outflanked or surprised but at least at Cannae they had a chance to hold out. Yet unfortunately the ground at Cannae, though narrow enough to prevent the Roman and allied cavalry from being outflanked, was also ideal for maneuverability and Hannibal’s more nimble and sophisticated forces used it to defeat the more cumbersome Roman army.

The Roman army at this time was led by two consuls, who shared command by exercising control of the army on alternate days. During the battle itself command was exercised by Gaius Terentius Varro, who was stationed with the allied cavalry, while his co-consul Lucius Aemilius Paullus was stationed with the Roman cavalry. The Romans typically placed their leaders in positions that were considered critical and it is no surprise that both consuls were placed on the flanks where the Romans were outnumbered and outclassed by the Carthaginians. Likewise Hannibal positioned himself in the centre, with his hard pressed infantry, to motivate them to hold out long enough for his cavalry to turn the tide of battle.

On August 2, 216 B.C, Varro, who was determined to bring Hannibal to battle, and who held command of the Roman army that day, decided to cross the river and deploy his army for battle. Hannibal, who had been hoping for a chance to decisively destroy another Roman army since Fabius’s days of delaying, took up Varro’s challenge and met the Romans on the field. As stated above, Varro deployed his army between the Aufidius River and the hilly terrain near Cannae in the hopes that his inferior cavalry would not be outflanked and would be able to hold out long enough until his massive Roman infantry force would overwhelm the significantly outnumbered Carthaginian infantry in the centre. Likewise, Hannibal’s plan was for his infantry in the center to fight a delaying action long enough for his cavalry to rout their opposite numbers, and then with the help of his Libyan infantry, completely destroy the Roman infantry.

As such the Romans deployed with their allied cavalry on the left, their infantry in the centre, and the Roman cavalry on the right. While it is hard to determine precise figures, most sources suggest the Romans had perhaps 3600 allied cavalry, 70,000 infantry and, 2400 Roman cavalry on the field itself, and perhaps 10,000 leftover or garrison troops in the camps nearby. Simultaneously, Hannibal deployed his army opposite the Romans and had his Numidian (or light cavalry) on the right to oppose the allied cavalry, his infantry (Gauls, Spanish and Libyans) were in the centre, and his Spanish and Gaulish (or heavy cavalry) were on the left to oppose the Roman Cavalry. As for numbers, most accounts suggest Hannibal had 40,000 infantry and 10,000 Cavalry (the lion-share of which were with the heavy cavalry on the left). If these figures are correct Hannibal fought the battle at Cannae outnumbered by 50%.

A few important considerations should be noted. Firstly, as stated many times above, the Carthaginian cavalry on the flanks both outnumbered and outclassed their Roman equivalents. Secondly, despite the fact the Roman infantry significantly outnumbered the Carthaginians they were hamstrung by several handicaps. While the Carthaginians were deployed in loose and flexible formations the massive Roman legions were deployed in a dense phalanx formation where soldiers were simply deployed in ranks, one after another, with little room. Usually the Romans deployed in looser maniples and in 3 main lines (the Hastati, the Principes, and the Triarii). Generally the first line was composed of greener troops and there were spaces in between for the Principe line, composed of more seasoned soldiers, to advance into if and when the battle demanded. Finally, the last line was composed of the most experienced troops who could reinforce the first two lines if things became critical.

The Romans choose the phalanx formation for Cannae because it was ideal for a slogging match as it was close, dense, and had considerable staying power. However, it also allowed little maneuverability and only the men fighting at the front, or if they were in contact with the enemy on the sides, the flanks, could engage the enemy while the rest would be stuck behind their comrades waiting for them to fall in order to advance and fight the enemy. The phalanx would win in a slow battle of attrition if whomever used it had numerical superiority and could not be outmaneuvered on the battlefield. Unfortunately for the Romans at Cannae they enjoyed the former, but not the latter. Indeed, despite the fact his infantry were considerably outnumbered Hannibal, as will shortly be described, deployed and maneuvered them in perhaps the most economical means possible.

While both sides deployed on the field, the skirmishers and light infantry fought in the centre. Like most battles in this age the skirmishers inflicted little casualties and had little, if any, impact on the subsequent battle. As already stated the cavalry of both armies were stationed on the flanks, with the Roman cavalry facing Hannibal’s heavy cavalry and the Latin cavalry facing the light Numidian cavalry. Likewise the Roman infantry deployed in a dense, but unwieldy, Phalanx formation. However, Hannibal deployed the bulk of his infantry (composed of Gauls and Spaniards) in a looser, more maneuverable, formation. This was shaped as an ark, or arrow, pointed towards the centre of the Roman infantry. Finally his Libyan infantry, his best soldiers, were deployed as two phalanxes both behind, and on the flanks, of his central infantry force. The purpose of these unorthodox deployments will be described shortly.

The main battle opened with the Carthaginian heavy cavalry rushing its Roman equivalent while the Roman infantry pushed towards the front of the Carthaginian ark in the centre. Hasdrubal’s cavalry fought the Romans in close order rather than mounting a charge that was typical in this era. While his force did outnumber the Roman cavalry this advantage was not apparent as the narrow space of the battlefield only allowed him to deploy his advance forces against the Romans. However, in the event, his advance forces were enough as his better trained and motivated forces defeated the Roman cavalry, who were probably used to losing against the Carthaginians after 2 years, in a short but vicious fight that was fought significantly on foot. After routing his opposite number Hasdrubal, much to his credit, began to reform his cavalry forces for the next stage of the battle rather than pursuing the Roman cavalry. However, before this brief but decisive engagement ended, the Roman infantry in the centre met the advanced Carthaginian forces which were deployed at the centre of the ark pointing towards them.

Unlike the quick and decisive engagement between Hasdrubal and the Roman cavalry on the left flank the battle between the infantry in the centre would prove to be a slow, brutal, and attritional struggle. The Romans, being generally better equipped and enjoying superior numbers, inexorably pushed back the weaker Carthaginian forces who were both deployed and ordered to fall back as slowly as possible to allow their cavalry counterparts time to turn the tide of battle. Hannibal himself was in the centre with his brother Mago to motivate his men to hold out as long as possible. Trying to delay the Romans from bursting through the centre Hannibal ordered his echelons stationed back on both sides of his centre ark to not advance, but to wait until the ark pulled back and then fight the Romans at the same time. Thus, the Romans would have to fight harder and harder as it came up against a Carthaginian line that became stronger and stronger as it retreated and absorbed its rear echelons. The added benefit, of course, was that the rear echelons would be more fresh than the Romans who would become increasingly tired from advancing and fighting.

However, despite Hannibal’s brilliant deployment of his infantry, and his inspirational leadership, Roman numbers began to tell as their massive force first pushed the Carthaginian ark back until its echelons formed into a straight line, then pushed it outwards in the opposite direction, and then finally managed to break Hannibal’s Spanish and Gaulish infantry in the centre and began to rout the Carthaginian forces. But while the Roman infantry finally broke the Carthaginian centre and began pouring through, its legions were no longer organized fighting units, but a massive mob intent on pursuing what they thought was a defeated enemy. In the end they would be sadly mistaken, but meanwhile another decisive engagement was occurring on another flank of the battle.

The battle on the right flank between the Latin cavalry, led by Varro, and Hannibal’s Numidian light cavalry was generally a less exciting affair than the great clashes occurring on the left and centre flanks. Ironically, both sides had been ordered to merely hold their enemies long enough until the battle would be won at another point on the field. The fighting on this flank, unsurprisingly, developed into a stalemate as neither side had the ability, or the will, to decisively defeat their opposite numbers. Most of the combat on this flank initially consisted of the Numidians using their superior speed and maneuverability to quickly ride up to their Latin enemies, throw their javelins and retire before their enemies could close in and attack them. Given that Rome and Carthage saw this flank as a sideshow both sides saw such an indecisive exchange as acceptable.

This ancient version of a “phony war” ended abruptly when Hasdrubal’s heavy cavalry, having been wisely reformed for another decisive attack instead of pursuing the already routed Roman cavalry, descended upon the rear of the Latin cavalry. Varro and the Latin cavalry, seeing this new unpleasant development promptly fled the battlefield before Hasdrubal’s heavy cavalry managed to close in and inflict a single blow upon the enemy. While history has generally judged Varro’s conduct in a less than kindly manner, a few considerations should be noted before adopting an overly harsh view towards his actions.

Firstly, one should consider his position when the Latin cavalry fled; his forces were caught in between the hilly terrain at Cannae to his left, the Roman infantry to his right and the Numidian cavalry to his front. Had he not retired sooner his forces would also have been confronted by Hasdrubal’s cavalry to the rear. In effect, he and his forces would have been surrounded, encircled, and likely destroyed in a very short time. Given the actual developments currently, or soon to occur on the battlefield, it is all but certain that any delay an alternative decision to stand, fight, and die, made by Varro would not have given any meaningful advantage to Rome, or result in any less of a victory for Hannibal in the battle.

Secondly, it is probable that much of the criticism Varro has received throughout history is because Polybius, one of the main historians of the battle, was a benefactor of Varro’s co-consul Lucius Aemilius Paullus’s family. Considering the latter died in the battle (while Varro escaped and survived), and considering Paullus’s family had more status and power in Roman society than Varro’s it is no surprise that they could afford to find scholars and historians to put a good spin on Paullus’s conduct at the obvious expense of Varro’s reputation. While none of this suggests Varro’s conduct at Cannae was impressive or that he should not shoulder much of the blame for its outcome, to place all of the responsibility on him for Rome’s failure would be both unfair and academically dishonest.

Either way the result of the fleeing of Varro and the Latin cavalry was another important victory for Hannibal’s forces and ultimately proved decisive at the end of the battle. Hasdrubal allowed the Numidian cavalry to pursue the Latin cavalry and once again focused on reforming his disorganized heavy cavalry for one last purpose which would seal the fate of the Roman army at Cannae.

Meanwhile, the Roman infantry in the centre were still confident in their initial rout of the Carthaginian centre and pouring through the gaps in an attempt to destroy their enemies against the back of the river. As stated above, by this time the Roman legions breaking through in the centre were no longer organized fighting units but mostly a blood lusting mob advancing towards what was thought to be a defeated opponent. Unfortunately for them Hannibal had been expecting such an outcome and had placed his Libyan infantry, his equivalent to Napoleon’s Imperial Guard, in positions both behind, and to the flanks, of the Carthaginian centre in two extended phalanx formations.

These Phalanxes were perfectly positioned to counterattack the Romans in the centre as they were deployed in considerable depth (as opposed to the regular Carthaginian infantry that had been deployed in a linear fashion to face the Romans) and the Roman forces passing in between the two flanks were now disorganized, well forward and exposed. Not only were the Libyans Hannibal’s best infantry, but they were also better equipped than their Carthaginian colleagues, having looted the Roman dead from Trebia and Trasimene. This likely played in their favor as many of the Romans were confused that similarly dressed soldiers as themselves were advancing towards them via the flanks.

Once the Romans in the centre had moved sufficiently into the trap the Libyan formations on both their flanks turned and advanced to attack. The Libyan phalanxes soon made contact with the Romans pouring through the centre and quickly stopped what had been the latter’s considerable momentum. This result was hardly surprising as the Libyans were veterans, in good order, and were still fresh as they had not yet been involved in the fighting, while much of the Romans were composed of greener troops, were hopelessly disorganized, and were considerably tired after heavy fighting. This latest maneuver by Hannibal regained the initiative for the Carthaginian infantry as it allowed the erstwhile retreating Spanish and Gallic infantry in the centre the chance to reform and re-join the battle line, as well as putting the Roman infantry, now surrounded on 3 sides, onto the defensive. The Romans were now gripped in a metaphorical vise, and having no effective reserves (having thrown all available forces towards the centre to accomplish their initial breakthrough) struggled to form coherent lines of defense.

If this were not enough, Hannibal’s army was now poised to unleash its last impressive maneuver upon the hapless Romans. By now Hasdrubal, having sent the Numidian cavalry to pursue the Latin cavalry, had once more reformed his heavy cavalry and proceeded to launch it in several devastating charges against the exposed Roman rear. This sealed the fate of the Romans as they were now more or less surrounded and had no room, or time, to organize their massive mob of fighting men into effective formations.

At this point the conduct of the battle became nothing more than a protracted, and attritional, slaughter. There were to be no more brilliant maneuvers, feigned withdrawals or major tactical decisions; just organized butchery. Apparently, this final stage of the battle was anything but brief and lasted most of the day until a very small portion of the original Roman army decided, or was allowed, to surrender.

Perhaps it is not surprising that most scholars of Cannae have focused predominantly on Hannibal’s amazing maneuvers and have usually glossed over this last part of the battle where in fact the vast majority of Romans were killed. No doubt it was more convenient to look at a map and think of the battle in terms of arrows and statistics than to imagine the sheer hell it must have been for the hapless Romans as they were trapped, stalked and hacked to death. Such scholars probably find it unsettling when historians such as Robert O’Connell describe how “at the end of the fight, at least forty-eight thousand Romans lay dead or dying, lying in pools of their own blood and vomit and feces, killed in the most intimate and terrible ways, their limbs hacked off, their faces and thoraxes and abdomens punctured and mangled.” However it would be foolish and dishonest to deny that Cannae’s enviable place in military history was bought, like all other feats in military history, without considerable human misery, suffering and death.

All of this suggests that Cannae would be a model of Clausewitiz’s school of military thought and not Sun Tzu’s. Admittedly, Hannibal was a master of maneuver, deception and knowing the enemy, three things constantly emphasized by Sun Tzu. However, Hannibal’s focus on destroying the enemy army, his deliberate use of maximum violence, and his primary focus on winning battles, are all staples of Clausewitizian doctrine. Sun Tzu, who cared more about maneuver and attempting to win without fighting wrote that “a surrounded army must be given a way out.” Unfortunately, for the Romans, Hannibal had no intention of letting them escape at Cannae and instead slaughtered them in a more Clausewitizian fashion. Hannibal’s maneuvers during the battle were simply means by which he could later kill as many Romans as possible, not to win the war with as little violence as possible.

As for results, Hannibal, despite operating with few supplies in a hostile country, and despite being outnumbered by 50% had not only defeated, but virtually surrounded and destroyed, a considerably superior enemy force. Cannae would prove to be Hannibal’s greatest battlefield victory and turn him into a legend.

The statistics regarding the battle are staggering to look at, especially if we remember that Cannae occurred nearly 2200 years before the horrors of the “First and Second World Wars.” In one day, the Roman army lost between 50,000 and 80,000 men and horses. Such discrepancies depend upon the sources, the difference between counting Romans who were captured on the battlefield versus those captured the next day at the Roman camps, estimations between wounded and dead, etc. Yet despite such varying estimates there are a few telling points.

Firstly, it seems as though the majority of Roman casualties were deaths; as in most of their army did not surrender. Secondly, including those who were killed, captured, wounded, or escaped, the vast majority of the Roman army was effectively eliminated at Cannae. In fact, in the end the Romans managed to scrape together perhaps 10,000 men (out of what originally may have been 86,000) who had not been killed or captured by Hannibal’s forces at Cannae, or in the surrounding area. Finally, as will be shortly noted, the casualty ratio was vastly in favor for the Carthaginian forces. All this Hannibal accomplished against a force that outnumbered him by 50%. If Roman losses from 218-216 B.C. including the disasters at Trebia, Trasimene, and other skirmishes and fighting are added the potential Roman military casualties thus far in the conflict ranged between 100,000-150,000. Considering Rome and her allies supposedly had 700,000 men available for war, and considering many of Rome’s allies would in fact shortly defect to Hannibal, it looked as though the Romans would eventually be bled to death.

To put it bluntly the Roman army at Cannae was destroyed as a fighting force, in both numbers and capabilities. In their long history Rome would suffer maybe one of two military disasters on such a scale. Meanwhile, the Carthaginian casualties have been estimated between 6500-8000, although this is unsatisfactory as there is no confirmation if these are total casualties, including wounded, or just deaths.

A few mores statistics help illustrate Hannibal’s victory at Cannae. No less than 1 consul (Paullus) 1 pro-consul, 2 Quaestors, 29 military tribunes, 80 senators, and a number of ex-consuls, praetors and aediles perished in the battle. Besides the slaughter of such a significant number of soldiers the Roman defeat at Cannae also deprived the republic of a high proportion of its military and political leadership. To put it in perspective imagine what would have happened if Hitler had not halted outside of Dunkirk but instead captured and destroyed the bulk of the B.E.F. in France in 1940. As most of Britain’s subsequently best generals escaped as well, it is interesting to wonder how different the war would have been had they been captured.

Why did Hannibal win the “Battle of Cannae?” Certainly there are no lack of factors that led to his victory. The terrain, though initially chosen by Varro to offer some protection for his outclassed cavalry forces, ultimately favored Hannibal’s cavalry instead. Additionally, Hasdrubal, the Commander of Hannibal’s heavy cavalry, deserves much credit for not only quickly dispatching first the Roman and then the Latin cavalry, but wisely refraining from pursuing either of them and focusing instead on quickly reforming his forces for more important purposes on the battlefield.

Hannibal himself correctly anticipated how the Romans would deploy and act and deployed his own forces in perhaps the most economical means possible to give his outnumbered forces the best possible chance to succeed. His use of forward echelons for his Spanish and Gallic infantry to give them staying power and time, the deployment of the majority of his cavalry on the left flank to quickly overwhelm the weaker Roman cavalry vs. the stronger Latin cavalry on the right, and his placement of the Libyan phalanxes behind his main infantry line to trap the Roman infantry as they burst through his centre were all brilliant stratagems.

On the other side, and with the benefit of hindsight, the Romans did much to hurt their chances of prevailing. As already stated, Varro’s decision to fight at Cannae due to the terrain was theoretically sound but proved to be disastrous in practice. Likewise, while the Roman decision to deploy in a colossal phalanx formation was both simpler for their inexperienced army and gave them much staying power, it was wasteful (as most of the troops would be deployed too far back to do any fighting) and offered little chance for maneuver; which ultimately reduced the Roman legions into little more than a rambling mob when confronted by Hannibal’s maneuvers. Additionally, the Roman plan for the battle was anything but subtle: Hold on the flanks with the cavalry long enough for the massive infantry force in the centre to crush its weaker Carthaginian equivalent.

It was a simple, and obvious, plan and while Adrian Goldsworthy in his brilliant books on Cannae and the “Punic Wars” reminds us that there were many ways that Hannibal could have lost the battle it is hard not to contrast the Carthaginian’s complex maneuvers with Rome’s frontal assault and the sheer imbalance of casualties and conclude that a potential Roman victory at Cannae was both unlikely and undeserved. There are plenty of examples of simple battle plans triumphing over elaborate ones in military history but Cannae was not among them.

Finally, besides the terrain, deployments and maneuvers, it is fair to suggest that at Cannae the Carthaginians generally had the advantage in leadership and experience. There was simply no Roman equivalents to Hannibal and Hasdrubal, men who had been engaged in constant warfare in Spain for years while the nature of Rome’s system of governance precluded its leaders would command for more than a short period of time. Likewise, while many of his troops had perished from the march from New Carthage to across the Alps the cream of Hannibal’s army, once again veterans from years of campaigning in Spain, were clearly superior to the generally green militias Rome mobilized infrequently. While it should be noted the Roman army at Cannae did have some experienced legions that had fought against Hannibal, or served under Fabius Maximus, there is no doubt that Hannibal’s forces were generally better led and more seasoned.

As for the strategic results of Cannae these can be categorized between what Hannibal’s victory accomplished in both the short and long term. In the short term it finally accomplished what Hannibal had been seeking since his descent of the Alps in late 218 B.C; the desertion of several Roman allies and a secure base of operation. Rome was further weakened by the entry of Macedonia into the war on the Carthaginian side, as well as defections to Carthage in Roman occupied Sicily and Sardinia. Theoretically such a defeat, and subsequent shifts in the strategic situation should have either resulted in a Roman surrender, unconditional or negotiated, or ultimate Roman defeat in the war.

However, it did not. Instead of coming to terms Rome shrugged off its losses and revitalized its war effort. Finally realizing the folly of engaging Hannibal’s superior forces head on Rome adopted an indirect strategy to combat Carthage. This involved wearing down Carthage by winning the military context in Spain and Sicily and then invading North Africa and bringing the war to Carthage itself. This was ironically helped by Hannibal’s new position after Cannae where he was responsible for guarding his new allies in Italy. This limited his mobility as he had to ward off sieges and attacks against Rome’s deserting allies and while he still managed to inflict some impressive defeats against Roman forces he never again achieved the decisive results gained from 218-216 B.C.

While Hannibal remained undefeated in Italy, in the end the worsening situation of Carthaginian forces in North Africa forced him to return home in a last ditch attempt to stave off defeat in 202 B.C. Here he faced Roman forces under Publius Cornelius Scipio, who had emerged as Rome’s best general of the conflict. The last great battle of the war occurred at Zama and while not as memorable, or sophisticated, as Cannae it was still similar to it in a notable way. While Scipio and Hannibal’s infantry fought a mostly attritional battle the Roman cavalry, supplemented by deserting Numidians routed Hannibal’s army and effectively won the day. This battle sealed the fate of Carthage and Rome triumphed in the “Second Punic War.” Thus in the long term, Cannae did not result in a Carthaginian victory.

There has been some controversy as to whether or not Hannibal wasted his victory at Cannae by camping near Capua and securing his gains instead of marching directly on Rome after the battle. While this seems like an attractive “what if scenario” it was both unlikely and unrealistic. It was unlikely because Hannibal’s set strategy from the beginning was to isolate Rome from its allies, and unrealistic because not only was Rome too far away from Cannae (perhaps 250 miles) to warrant the likelihood of a successful march, but his army was also considerably weakened from its losses in the battle and finally Hannibal did not have the means to launch an effective siege of Rome. Some authorities on the subject have suggested that the mere presence of Hannibal at the gates of Rome after Cannae may have been enough to scare Rome into surrender but this ignores both the stubborn nature of Roman society and the fact that a later Carthaginian incursion near Rome in 211 B.C. had little effect on Roman morale. It is possible that an all out effort against the city of Rome by Hannibal after Cannae may have won him the war, but the odds were considerably against it.

As for Hannibal himself, while he remained in Carthage for sometime after the conflict and held high office in an attempt to re-establish Carthaginian power and prestige, a combination of Roman antagonism and political rivalry eventually forced him into exile. However, this was not enough for the Romans who were terrified of Hannibal and constantly paranoid that he would somehow raise another army to attack them again. Therefore he spent the last years of his life pursued by Roman agents until he was finally cornered in modern day Turkey more than 3 decades after Cannae. Rather than face capture and the potential ridicule of being paraded in Rome Hannibal poisoned himself and left a note which read “let us relieve the Romans from the anxiety they have so long experienced, since they think it tries their patience too much to wait for an old man’s death.” This was the fate of Rome’s greatest enemy.

Then, there is the disproportionate affect Cannae has had upon subsequent military theory. Needless to say, and given Carthage’s eventual defeat in the conflict, the predominant focus of subsequent generations of military theorists has been upon explaining, and codifying, the reasons for Hannibal’s unequivocal tactical victory at Cannae versus the final strategic results of the war. Soldiers are generally practical and straightforward by nature and not surprising given the threat of death usually look at solutions that provide immediate results. Perhaps it is no secret that victory in battle is often the key to victory in war, but such a narrow focus on the tactical and operational levels can cheat soldiers when even overwhelmingly tactical results on the battlefield do not transform into decisive political or strategic effects with the potential to end the war on their side’s terms. Hannibal himself was a shrewd politician and strategist, and the fact that he ultimately lost despite being a master of war at all levels should have been a sober reminder to succeeding generations of soldiers.

Unfortunately, the most important lesson of Cannae, that even a perfect tactical victory does not necessarily lead to decisive political effects to end hostilities, has been lost upon countless soldiers, and politicians, throughout history.

A look at some of the more brilliant military tactical victories of the last 2 centuries confirms this. The German encirclement of Soviet armies at Kiev in 1941 may have netted the greatest number of prisoners in the history of war up to that point in time, but it also meant that the subsequent effort against Moscow would be frustrated due to the arrival of the Russian winter. Likewise, the completely one sided victory Israel achieved against Syria’s SAM (surface to air missile) batteries and Air Force in 1982 in the Bekaa Valley did not allow her to pacify Lebanon and secure her northern border. Even Nelson’s famous triumph at Trafalgar had limited strategic success; while it secured England against invasion it did not stop Napoleon from gaining his greatest victory at Austerlitz, or dominating most of Europe for another decade.

Tactical triumphs that have led to decisive political successes are even rarer in unconventional warfare. The unequivocal American success against the “Tet Offensive” in Vietnam in 1968, France’s harsh methods that all but destroyed the F.L.N. insurgents in Algeria, and Israel’s countless tactical victories against Palestinian and other irregular groups since 1948 all failed to lead to a satisfactory peace, let alone victory. While it is easy for historians, or armchair generals, to cite a few examples and imply they prove their point, military history, especially the last 200 years, suggests that tactical victory does not determine political, or strategic success, on its own.

Yet despite this unpleasant truth, Cannae has been used as a model, or template, for soldiers for generations to find and seek a supposedly perfect battle to win their respective conflicts. Unsurprisingly, the Prussians, and later the Germans, who placed perhaps too much emphasis on winning the tactical contest in battle have shown the most interest in Cannae. Frederick the Great, Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, Alfred von Schlieffen, and countless German soldiers in both world wars fantasized about inflicting another Cannae. With a few exceptions, they failed.

Frederick the Great had his master-pieces at Rossbach and Leuthen but it was diplomatic luck, as in the death of the Russian Tsaritsa, and not battlefield prowess, that saved Prussia in the “Seven Years’ War.” Moltke’s victory at the “Battle of Königgrätz” during the “Austro-Prussian War” is admittedly both a tactical and strategic success as it quickly won the war, but victory would end up being more prolonged and costly for him in both the “Second Schleswig War” and the “Franco-Prussian War.” Alfred von Schlieffen is said to have been obsessed with Cannae, making countless diagrams and studying it in minute detail. Not surprisingly his plan to defeat the French in 1914 at the beginning of the “First World War” was said to be heavily based upon it. Unfortunately for Schlieffen his meticulous study of train schedules and tactics he hoped would grant him total victory floundered against political considerations (such as Britain’s entry into the war) and unforeseen circumstances (such as the sheer logistics of the endeavor and Russia’s surprisingly quick mobilization). Perhaps he would have been wise to heed Moltke the Elder’s dictum that no plan “survives contact with the enemy.”

Likewise, military history from both world wars shows a remarkable tendency on the part of the Germans failing to secure political and strategic success from considerable tactical victories. Somehow it did not matter how many Russians they killed, how many ships they sunk or how much territory they overran; the Germans still lost both conflicts. Certainly in “World War 2” the Germans had a few windows of winning, such as after the “Fall of France” or during “Operation Barbarossa,” but in general any objective strategist in their position would probably have questioned how much tactical success it would have required to win when they were fighting the whole world.

However, the legacy of Cannae was not limited to Germany. Its influence was so widespread among military circles that Dwight D. Eisenhower suggested that “every ground commander seeks the battle of annihilation; so far as conditions permit, he tries to duplicate in modern war the classic example of Cannae.” Even as late as “Desert Storm” General Norman Schwartzkopf, the commander of Coalition forces that liberated Kuwait from Iraqi forces, said “I learned many things from the ‘Battle of Cannae’ which I applied to Desert Storm.” While Schwartzkopf’s execution of the liberation of Kuwait was indeed a tactical equal of Cannae and led to a satisfactory peace in the short term, many of the seeds of the modern “War on Terrorism” were sown in that conflict that it could almost be suggested that the Coalition’s triumph over Iraq was a “pyrrhic victory.”

Yet not all great commanders fantasized about Cannae. Ironically, given his aggressive nature, General Patton seems to have been more realistic about the likelihood of duplicating Hannibal’s great feat. He once wrote “there is an old saw to the effect that: ‘To have a Cannae you must have a Varro’…in order to win a great victory you must have a dumb enemy commander.” While the controversial case against Varro has been discussed above, there is no doubt that the greatest military victories in history have usually been as much of a result of incompetence on one side as brilliance on the other.

None of this is to suggest that Cannae was not a decisive victory, that Hannibal was an ineffectual commander, or that tactical success should be underestimated in war. Obviously wars are generally won by success on the battlefield. Hannibal’s victory at Cannae against superior forces was indeed a rare, and imaginative, phenomenon in military history and there was nothing wrong with succeeding generations of soldiers studying and trying to imitate it. However, despite such a lopsided victory Hannibal eventually lost the war and it merits questioning why the reasons for his ultimate failure have never been studied by soldiers with the same degree of thoroughness or enthusiasm as they have regarding his tactical successes. War is a comprehensive activity and as Clausewitz noted “the political object is the goal, war is the means of reaching it, and means can never be considered in isolation from their purpose.” Tactical victory on the battlefield is an important, usually critical, factor for victory in war, but if it does not lead to favorable strategically or politically results its greatest legacies usually remains in books instead of favorable outcomes at peace conferences. Unfortunately for Hannibal, this was to be the fate of his greatest triumph at Cannae.

Bibliography

Bagnall, Nigel. The Punic Wars: 264-146 B.C. Oxford: Osprey, 2002.

Fields, Nic. Hannibal. Oxford: Osprey, 2010.

Goldsworthy, Adrian. Cannae. London: Cassell, 2001.

Goldsworthy, Adrian. The Fall of Carthage. London: Cassell, 2004.

Goldsworthy, Adrian. Roman Warfare. London: Cassell, 2000.

O’Connell, Robert. The Ghosts of Cannae. New York: Random House, 2011.

Article from “Roman Empire”: The Battle of Cannae. http://www.roman-empire.net/army/cannae.html

Article from “The Romans”: Battle of Cannae. http://www.the-romans.eu/battles/battle-of-cannae.php

Wikipedia article on the “Battle of Cannae”: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Cannae [December, 2013]