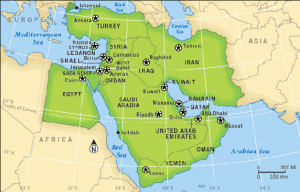

“Arabs at War” is among the great books on conflict and history regarding the modern Middle East. In this work Kenneth Pollack, a former CIA analyst, sets out to answer a simple question; “why have Arab armies since 1948 generally performed so poorly in warfare compared to Western, Israeli, and even Iranian and African armies?” He studies the performance of Six Arab armies (Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Libya, Saudi Arabia and Syria) in countless conflicts over the last 5 decades and tries to determine their strengths and weaknesses. Using traditional theories as to why Arab armies are generally ineffective he breaks down Arab combat effectiveness according to certain criteria. These include generalship, tactical leadership, unit cohesion, cowardice, morale, information management, technical skills and weapons handling, logistics and maintenance of weapons, and training. Analyzing these military conflicts to see how these factors influence Arab combat effectiveness, or lack of it, is how Pollack tries to answer “why Arab armies fight so poorly?”

“Arabs at War” is among the great books on conflict and history regarding the modern Middle East. In this work Kenneth Pollack, a former CIA analyst, sets out to answer a simple question; “why have Arab armies since 1948 generally performed so poorly in warfare compared to Western, Israeli, and even Iranian and African armies?” He studies the performance of Six Arab armies (Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Libya, Saudi Arabia and Syria) in countless conflicts over the last 5 decades and tries to determine their strengths and weaknesses. Using traditional theories as to why Arab armies are generally ineffective he breaks down Arab combat effectiveness according to certain criteria. These include generalship, tactical leadership, unit cohesion, cowardice, morale, information management, technical skills and weapons handling, logistics and maintenance of weapons, and training. Analyzing these military conflicts to see how these factors influence Arab combat effectiveness, or lack of it, is how Pollack tries to answer “why Arab armies fight so poorly?”

The result is a brilliant, informative, and enlightening work that effectively answers what it sets out to and also doubles as an authoritative, if brief, military history of the Middle East since 1948. Being a former CIA analyst Pollack is skilled at delving into the most important details as well as coming back to the bigger picture when needed. Yet whereas some would perhaps criticize this work as overly academic and dry his arguments and points are simple enough for anyone with basic knowledge of military matters and the Middle East. While admittedly it is not the easiest, or shortest, of reads, anyone with a mediocre level of patience can navigate through it. If the campaigns and battles can sometimes seem confusing Pollack compensates by listing the main points at the end of each conflict as well as relating them to the criteria he uses to assess Arab military effectiveness.

As for the case studies themselves they include a menagerie of well known and lesser well known conflicts, and combat ranging from conventional wars, to counter-insurgency, to low scale skirmishes and aerial combat. The “Arab-Israeli Wars” the “Iran-Iraq War” and the “Gulf War” are all here while more forgotten conflicts such as the “Chadian-Libyan Conflict,” Egypt’s intervention in Yemen in the 1960s and Jordan’s suppression of the PLO in 1970-71 are covered as well. Aerial combat has not been neglected either; the surprise attack that crippled the Egyptian Airforce in 1967, the slaughter of the Syrian Airforce over the Bekaa Valley in 1982, and the hopeless plight of the Iraqi Airforce during the “Gulf War” are all vividly detailed.

Pollack does a great job of showing how the Arab armies learned, or didn’t, from their mistakes and the methods they used that increased, or once again didn’t, their military efficiency. Obvious methods included switching the primary task of the armed forces from regime protection (often the preference for illegitimate authoritarian governments) to focus on fighting actual wars, to selecting officers and generals on the basis of merit and competency instead of political loyalty, and to encourage initiative, flexibility and innovation among the junior officers in their armies. Unfortunately, and perhaps predictably, these and other reforms usually resulted in only marginal improvements in Arab military effectiveness.

While it is never directly stated, and thus remains one of the main faults of the book, it is implied that certain cultural or organization factors in Arab society somehow prevents Arab military leaders, despite their best efforts, to create and maintain effective armed forces. Whether or not this is due to the lack of separation of Church and State (or at-least downplaying the former’s role in society) in the Arab world, the inherent mistrust among differing levels of society that precludes harmonious working in organizations, the result of poor education systems, the supposed Arab psyche to save face and avoid confrontations or competition, or all of these and more in combination we are not told. While the author suggests that he was originally going to write a book that included such insights and factors he claims that such a book was not allowed to be written due to how long it would have been (more than twice as long as the 600 page book that “Arabs at War” became).

Perhaps this is reasonable enough in itself; certainly a book of over 1200 pages is a real trial for even the most dedicated reader, and arguably unbearable for such a complicated work that would include such seemingly diametrically opposing fields as military matters and sociology. However, are we to believe that in a 600 page work the author could not have devoted a single chapter, or even 5 pages to the supposedly crucial cultural or organizational factors in Arab societies that arguably are responsible for the poor showing regarding the criteria he sets out to prove how Arab armies have performed so poorly in combat? More likely commenting critically on such hot topics as Arab culture and Islam would have been met with being labelled as politically incorrect at best, or having Pollack threatened with violence at worst. Given how even a cartoon in a Danish newspaper can inflame the masses in the Middle East and lead to bloodshed this consideration should not be discounted.

Anyway, putting this aside Pollack does a great job narrowing down which of the criteria he initially selected is primarily responsible for the poor showing of Arab arms since 1948. While not always universal in all Arab armies, and it varied at certain times, the following could reasonably be stated:

Regarding unit cohesion, logistics and cowardice the Arab armies rarely suffered from such issues. Generally their units held together despite considerable pressure, being flanked or even surrounded. There were countless examples from the Egyptians in the Falluja pocket to the Jordanians at Ammunition Hill of Arabs fighting and dying instead of retreating, or surrendering, despite hopeless odds. Additionally, Arab logistics were almost always outstanding. Egyptian forces fighting in the hostile Negev or Sinai deserts rarely suffered shortages while the Libyans adequately supplied their forces not only more than 2000 kilometres away from Tripoli to the interior of Chad, but as far away as Uganda! Finally most Arab forces could never be considered cowardly; few forces would have continued to advance to certain suicide as Iraqi tanks did on the Golan Heights in 1973 or few pilots would have kept coming as the Syrians did in 1982 when the Israelis slaughtered their jets so brutally that they lost nearly 100 planes to none against the Israeli Air Force.

Regarding morale, training and generalship Pollack suggests that the Arabs were generally mediocre in these categories; being quite capable sometimes and very poor at others. Morale is difficult to gauge but certainly the Arab armies fluctuated from intense optimism to fatalistic defeatism. In 1948 the Arabs were enthusiastic in their goal of eradicating the nascent Jewish state, and in 1973 the Egyptians and Syrians were well motivated after intense training and preparations for war. Yet there were just as many low points for the common Arab soldier such as the tired, and confused, Egyptian soldiers being constantly moved around the Sinai in 1967 before the “Six Day War” to no apparent purpose, or the thoroughly demoralized Shiite conscripts of Saddam’s army in 1991 that had being abused by the Sunnis in power, bloodied by the Iranians in the recent “Iran-Iraq War” and psychologically devastated by the Coalition air campaign.

Training was generally the same story, with the Jordanian army in particular being praised. Apparently the average Jordanian soldier, tank crew and pilot were often as good as their Israeli counterpart. Factors which influenced the quality of training generally included if the political leadership wanted the army to focus on regime protection or fighting real wars, whether the officer and generals were more selected due to competency than political loyalty, if the soldiers were allowed to train in large groups with live ammunition (Arab regimes were afraid these forces could overthrow them), how often and how thorough the soldiers were trained in a particular task, etc. When these conditions were met Arab training could produce above average results.

Certainly Jordanian units consistently inflicted more casualties proportionately on Israeli forces than other Arab forces in 1948 and 1967 as well as in other smaller skirmishes. Likewise the constant Egyptian training leading up to the “Yom Kippur War” lead to perhaps the greatest tactical reverses the Israeli army has ever received in battle. Finally, improved Iraqi training late in the “Iran-Iraq War” helped their army inflict quick and decisive victories in 1988 which broke the stalemate and ended the conflict.

Yet Arab training has been just as often, or more often, atrocious and poor. Regarding the overly politicized army the Egyptians sent to the Sinai and their comprehensive defeat in 1967 Egyptian General Zaki remarked “Israel spent years preparing for this war, whereas we prepared for parades.” The Syrian army on the Golan heights in the same war had been so decimated by years of coups, of its officer corp being purged repeatedly and of its lower formation being neglected and forgotten that few soldiers had any idea of what war was supposed to be like. Libyan forces were probably the worse off with Gaddafi refusing to allow live fire training exercises or establishing formations larger than brigades. How else could you explain his considerable army of tanks, planes and half-tracks being defeated by Chadian rebels with Toyota pick up trucks, a few anti-tank weapons and no air force in the late 1980s?

The Arabs have also had an uneven track record with generalship. Yet again much of this had to do whether or not they were chosen due to competency or political loyalty. Another factor was whether or not competent generals were given leeway to do their jobs versus being subject to unnecessary political constraints, and at least as was often the case in the Iraqi or Syrian armies, the fear of summarily execution. While they never produced any Alexanders, Napoleons or Rommels the Arabs surprisingly had a decent amount of competent, and sometimes brilliant, generals. Egypt’s generals arguably would have won the “Yom Kippur War” had they not being overruled by Sadat to overreach themselves and get clobbered by the Israelis in the open Sinai desert. The Iraqi generals, once freed from Saddam’s paranoia, also performed well in first stopping the Iranian offensives in the middle part of the “Iran-Iraq War” and then leading Iraq to victory at the end of the conflict. Even in such a lost cause as the “Six Day War” the Jordanian leadership was competent, correctly identifying the Israeli axes of attack as well as the enemy’s intentions.

As for bad Arab generalship the poorly planned and dismissive way the Egyptian generals fought Yemeni rebels, the Iraqis generals fought the Kurds, and Jordanian generals initially attacked the PLO in 1970 all make America’s conduct in Vietnam appear credible. Iraq’s initial strategic conduct of the “Iran-Iraq War” was also subpar, being excessively slow, not focusing on any critical objectives, and not effectively using the various numerical and material advantages the Iraqi army possessed. Not surprisingly the worst showing, given that the Egyptians had significant advantages in both the quantity and quality of equipment, and could concentrate against Israeli whereas the latter was forced to watch 3 fronts, was probably the Egyptian generals during the “Six Day War.”

Despite the fact they were poor at maneuver warfare they deployed their forces in areas with poor static defences and concentrated far too close to the Israeli border which meant that once the Israelis broke through the Egyptians would have to retreat and fight the kind of war they were ill-disposed at. They also decided to retreat too early and did so in such a poor fashion that it quickly turned into a rout. Perhaps most unforgivable is how many of their generals simply abandoned their troops and were the first to flea across the Sinai.

Finally, regarding maintenance of weapons, technical skills and weapons handling, information management, and tactical leadership Arab armies more often than not did poorly. Arab maintenance of sophisticated weapons such as tanks and warplanes were so bad that such units generally operated at 50-67% operational readiness levels, which were considerably lower than in Western, or Israeli, forces. While once again Jordan was an exception and her weapons generally well maintained, the other Arab countries not only neglected such maintenance but often relied on foreign contingents, such as Cubans and East Europeans to do what they considered dirty and demeaning tasks.

Technical skills and weapons handling were also generally subpar. American and Western military advisors noted that Arab soldiers, tank crews and pilots took much longer to familiarize, or master (if they ever did) their equipment versus Western or even third world soldiers in other armies. Additionally, much of the time Arab soldiers used their weaponry inefficiently. Marksmanship and accuracy seems to have been generally poor even when they had better tanks such as Jordan’s Pattons in 1967 or superior artillery as some as Iraq’s were in 1991. In aircraft most Arab pilots were notoriously poor at close air support and aerial combat. According to many sources during the “Arab-Israeli Wars” the Israelis shot down at least 20 warplanes for every 1 they lost in dog fights (which doesn’t even count the 100s of Arab planes that the Israelis destroyed on the ground). Artillery was also a constant problem for Arab forces; while it did well if they had considerable time to pre-register their targets, as in 1973, it was hopeless whenever it had to fight a fluid and unscripted battle.

Regarding information management the Arabs misuse of information has been sometimes laughable and other times tragic. Such misuse has included the lack of sharing, or even gathering, intelligence, exaggerating the strength of enemy forces, and down right lying.

Arab forces have generally proven reluctant to gather intelligence by patrolling on the ground while their airforces have proven unable, or unwilling, to gather much from aerial reconnaissance. Sharing information is also difficult as knowledge is often seen as power by higher officials and due to the often complicated communications networks set up by Arab leaders to keep their armed forces fragmented and easy to control. This can be contrasted by the American practice in network centric warfare where information is shared among rank and file and allowed to move quickly wherever needed in order to facilitate quicker decision making on the battlefield. Decisions that could be made quickly, and on the spot, by lower officers in Western or Israeli forces were usually made at the highest level in Arab Armies after they had first been passed all the way up and then later pushed all the way down in a process that often lasted hours. How could this ever be an effective way to wage war?

The exaggeration of enemy forces is hardly new in military history, but the Arab armies in the last few decades arguably perfected the art. Nearly every time units fled or were defeated in battle they said they had been grossly outnumbered, which is amusing considering most of the time Arab enemies such as the Israelis, Chadians, or even the Iranians, were usually the ones who were outnumbered.

Yet nothing is more comedic than when Arab leaders have lied to each other with disastrous results. Instead of admitting that the Egyptian Air Force had been destroyed on the first day of the war in 1967 Nasser told the Jordanians and Syrians that the Israeli Air Force had been destroyed and this fooled them into joining the war and sharing Egypt’s defeat. The Egyptians lied again during the run up to the 1973 War telling the Syrians they would advance deep into the Sinai when they merely intended to occupy a small part of the East Bank of the Suez Canal. They even made fake plans and showed them to the Syrians in order to get the latter to attack Israel. The Syrians also lied during the 1967 war when they claimed that the city of Quneitra had fallen which caused their forces in the Golan Heights to flee and allowed the Israelis to secure the heights before the ceasefire.

Yet according to the author it was the poor showing of Arab armies at the tactical level more than any other factor which explains why they did so poorly in warfare. In general Arab NCO’s were poor regarding initiative, innovation, using maneuver in warfare, executing combined arms operations, and found it nearly impossible to adapt to unforeseen circumstances on the battlefield. As such the strategic leadership of Arab armies could not rely on their smaller tactical formations to gain them success in order to accomplish their goals during warfare.

Typical occurrences included a tendency to conduct costly frontal assaults (such as the Iraqi tanks on the Golan Heights or Syrian tanks in Jordan in 1970), to fight off attacks from fixed positions even when launching a counterattack was the best option (such as the Syrians on the Golan heights in 1967 and the Jordanians fighting around Jerusalem during the same war), and an inability to effectively coordinate tanks, infantry, artillery and airpower as a team (often tanks and infantry would fight separately while artillery and air support would be notoriously inaccurate).

However, this was not always the case. The Jordanian Arab Legion had brilliant tactical leadership during the 1948-49 war and stopped the Israelis from conquering the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Yet Pollack shows us that this was actually the result of the Arab Legion having seasoned British officers and that once these officers had been kicked out of Jordan in 1956 Jordanian forces slowly degenerated and suffered from the same tactical handicaps as other Arab armies.

These key flaws, especially lack of effectiveness in tactical leadership have proven so detrimental that it has caused the Arab armies to lose many battles and wars despite having considerable advantages in numbers and quality of equipment. In the Sinai in 1967 the Egyptians had 100,000 troops, 1000 tanks and 450 planes vs. Israel’s 70,000, 700 and 200 respectively. Regarding quality the Egyptians also generally had better tanks, APCs (armoured personnel carriers), artillery and even infantry weapons. Yet during the war Egypt lost perhaps 15,000 casualties and 500 tanks while the Israelis lost 1400 and 60.

Likewise during the same conflict the Syrians on the Golan Heights outnumbered the Israelis at least 2-1 in troops, and the same in tanks. Additionally they had formidable defences built into the excellent terrain of the heights as well (and the Israelis had no other option than to launch a frontal assault). Regarding quality the Syrian tanks were also more modern than the Israeli ones. Yet the Israelis took the the heights in a mere 2 days and inflicted a 10-1 casualty ratio on the Syrians.

Iraq also failed to make significant gains against Iran in 1980 despite the chaotic state of the latter country after the Iranian revolution and enjoying a 5-1 advantage in tanks, a 4-1 advantage in artillery, and 3-1 advantage in aircraft. The Iranians also had significant problems with personnel and equipment as many of their soldiers and pilots had been arrested and embargoes by Western powers denied Iran crucial supplies for their weaponry. Yet Iraqi forces were slow, indecisive and failed to secure any notable objectives in the first year of the war and were eventually thrown out of Iran by mostly ill-equipped Iranian forces of fanatical soldiers who enjoyed few modern weapons.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the book is in describing how certain Arab leaders recognized the flaws of their officers and soldiers and developed plans and means that led to some improvement in their tactical prowess, and thus more success in war.

The first step, as constantly noted above, was a gradual de-politicization of the armed forces, where generals began to be selected more by merit than by political loyalty. This worked better in Egypt and Iraq than in Syria. This allowed better generals to take command and formulate war plans that took into account the inherent flaws of the NCOs and soldiers in their armies. The main problems according to the generals was that the lower officers were unskilled in combined arms operations, had little initiative and flexibility, were atrocious at managing information (as in they constantly lied or exaggerated) and poor at maneuver or fluid battles where they had to adapt quickly to unseen difficulties.

It is fascinating how Egyptian, Iraqi and Syrian generals found ways to compensate for these flaws. In essence they micromanaged set piece assaults that were suppose to be quick, decisive, and last no longer than a few days. The battle plans, the preparations and even the most tedious and small tactical movements to be executed by privates were planned down to the lowest details. The generals did their best to plan combined arms operations and maneuver into the NCOs’ and soldiers’ orders to compensate for their inefficiency in these matters. The obvious flaw in this was that as Moltke the Elder said “A battle plan never survives contact with the enemy.” In other words in a fluid and unpredictable endeavour such as warfare it is nearly impossible to plan for everything and unforeseen circumstances will always unravel the best preparations.

Yet the Arab generals understood this and they tried to compensate using a few stratagems. To them the keys were establishing complete surprise, attacking in overwhelming numbers and to launch and finish their operations in a short time. Obviously the former two considerations would keep the Arab’s enemies off balance and on the defensive while the latter one would hopefully deny the enemy the chance to regroup and regain the initiative.

They also realized that given how poorly their lower formations collected intelligence that they needed to make a sincere and collective effort at the higher end to do so in order to be able to have enough information on the enemy’s strength and disposition, and the battlefield to plan quick, local and decisive attacks.

The best examples of such attempts by Arab generals to win wars by compensating for the inefficient tactical leadership of their lower officers were demonstrated by the Egyptians, and to a lesser extent the Syrians, during the 1973 war and the Iraqis during the final stages of the “Iran-Iraq War.”

These campaigns featured the best means by which Arab forces found a relatively effective way to wage conventional warfare in modern times.

This included:

-the micromanagement of lower formations to guarantee they could accomplish basic tactical procedures with an acceptable degree of competency

-constant and thorough training of troops down to the lowest level regarding even the simplest of task in order to guarantee they could execute their tasks by familiarization and memorization

-quick, limited and decisive operations to allow their forces the best chance of success before the enemy had time to regroup and attack and because longer offensives were simply too unrealistic to plan given the limited means of Arab tactical leadership

-robust intelligence gathering to allow adequate planning

-establishing strategic surprise and attacking with overwhelming numbers so that the enemy was kept off balance and had little chance to upset the delicate micromanagement of the Arab war effort

The first instance, that of the Egyptians in the 1973, is perhaps the best known and the most celebrated, especially by the Arabs. Not only did the Egyptians quickly seize the East Bank of the Suez Canal, but they also thoroughly bloodied the Israeli army during the latter’s initial inept counterattacks as well as bringing the Israeli Air Force close to the red line by shooting down and damaging a disproportionate amount of their planes. As stated above the Egyptians probably could have held onto their initial gains and won the war if Sadat had not ordered the army to overreach themselves and get slaughtered in the open desert.

The Syrians also managed a better than average showing of Arab arms in 1973 when they nearly succeeded in re-conquering the Golan Heights. While they did not show the same tactical prowess or thoroughness of the Egyptians they did manage to achieve strategic surprise and overwhelming numerical supremacy at the point of attack. In fact the Israelis managed only stem a Syrian breakthrough into Northern Israel by incredible bravery, brilliant tactical leadership and luck.

Finally, the Iraqis managed to end the 8 year “Iran-Iraq War” by a series of well planned and executed set piece assaults. These offensives were designed to be local, just over the Iranian border, to last a matter of days, and to focus on destroying what remained of the heavy equipment of the Iranian army. Iraqi intelligence and staff work was impeccable and the Iraqi forces followed the detailed instructions from their generals to the letter and routed the Iranians forces time and again until the latter, being war wearied, low on weapons and internationally isolated, agreed to a ceasefire.

This was the best that Arab arms, with the aforementioned exception of Jordan’s Arab Legion in 1948-49, ever accomplished. There were to be no brilliant Blitzkriegs like the “Battle of France in 1940,” no spectacular coups such as “Inchon” in 1950, or innovative ad-hoc efforts such as the British re-conquest of the Falklands in 1982. Arab military performance from 1948-91 (the period Pollack covers in his work) in general was below average with a few notable instances of slightly above mediocre results.

If I can be forgiven for going off topic and going beyond Pollack’s work for a while events in the 21st Century would suggest that Arab armies have continued to stagnate. Syria and Iraq, arguably the two Arab countries with the most experience of warfare, are currently on the brink of collapsing to a menagerie of Al-Qaeda diehards, ISIS zealots and other terrorist or guerrilla groups all with different motives and capabilities. Despite Syria’s experience with crushing internal dissent and insurgencies, most notably the massacre of tens of thousands of people in Hama in 1982, her army seems destined to lose the war in the end. Iraq’s situation is more shocking given all the money, aid, weapons and training (in billions of dollars)

given to it by the United States. Apparently most of this was for naught considering a very small force of ISIS fighters has repeatedly beaten Iraqi forces who have had massive advantages in numbers, weapons and firepowers. It cannot help but make any rational person wonder what all the American money, blood and effort in Iraq was for?

Given the poor showing of Arab armies it is not surprisingly that there has been a transition from confronting Israeli, American or even Arab regimes with conventional warfare to terrorism and guerrilla warfare. While such groups have rarely succeeded in winning militarily they have scored several political victories such as briefly establishing the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, forcing the Israelis to withdraw from Southern Lebanon in 2000 due to public fatigue, and have arguably brought the regimes in Iraq and Syria to the brink as of 2015.

Yet it is doubtful whether this switch to reliance on unconventional means will ever yield decisive results for the Arab states or insurgent or terrorist groups. Their best accomplishments are in fact far behind them as Arab rebels in Algeria, Aden, and Lebanon forced colonial or western nations with little political capital for their Middle Eastern adventures to pack up and leave but unfortunately for guerrilla fighters and terrorists across the region the Arab regimes and Israel have no where to go and will fight to the death rather than surrender to them. As Norvell B. DeAtkine noted in a smart piece about Arab insurgencies “while the success of Arab insurgents against Western armies or those assisted by Western powers has been minimal, the success rate against their own governments has been zero.” This follows the logic that insurgents and terrorists rarely win, especially against domestic regimes (such as the Arab ones) or prosperous democracies (like Israel), that their victories are usually the result of a foreign occupier losing political will, and that it is extremely rare that they physically overthrow their oppressive government by military means.

This last point is especially true if the government has considerable foreign backing. Indeed South Vietnam and the Soviet backed regime in Afghanistan were never close to collapse as long as the superpowers supported them but quickly did once they stopped doing so. Given that the Russians are still propping up Assad and the Americans are still supporting the small minded politicians in Baghdad there is no reason that ISIS should triumph any time soon.

However, and while all of this has nothing to do with Pollack’s work (though he suggested near the end of his book that “someone else will have to write the long history of Arab unconventional forces in combat since 1948”) there is little doubt that Arab insurgents and terrorists have shown much more success in warfare than their conventional brethren; generally prolonging conflicts, eroding Western, Israeli and even Arab political will, and costing their enemies more money, blood and effort than the best Arab armies managed to.

Certainly even the traumatic experiences of “Israel’s War of Independence” and the “Yom Kippur War” have not been as divisive or caused as much soul searching for the Israelis as their long occupations of Lebanon and the Palestinians territories along with all the terrorism, counter-terrorism and questionable methods that have come with it. Meanwhile Saddam Hussein’s “Mother of all battles” in Kuwait and Iraq in 1991 was quick, cost America less than 500 deaths, resounded in an outstanding victory and was not economically ruinous for the United States. Yet the proceeding “Iraq War” was much longer, much more costly in financial and human terms and so far the overall results would seem to be… less than satisfactory. Finally, it is obvious that Arab leaders have always been more afraid of their own people and subversive groups than being toppled by the Israelis or Americans considering whereas the only time any of them were overthrown by the latter was in 2003 whereas there have been too many revolutions, popular uprisings and coups in the Arab world to count on even 20 pairs of hands.

“Arabs at War” is a key book to understanding the modern Middle East. Besides the obvious way in which it shows why the Arab armies have consistently failed to beat American, Israeli or other armed forces it also raises important questions as to the legitimacy of Arab leaders and governments given the underlying problems that plague the Arab world which prevent it from attaining political, economic or societal success (though this is done mostly indirectly). While the Arab world enjoys mocking Americans and Westerners for failing to learn from history Pollack shows the reader convincingly that given how Arab armies have consistently and irredeemably made the same mistakes since 1948 that the Arab World doesn’t exactly merit an A+ in history itself.

Yet despite the brilliant way Pollack uses his case studies and criteria to analyze Arab military effectiveness, no matter how accurate and damning are his conclusions, and no matter how vital his work is there are some notable flaws.

The most blatant, as noted above, was the failure, or reluctance to either thoroughly, or even cursory articulate the underlying cultural or organization factors in Arab society which facilitates the poor showing of their armed forces. This has already been explained but it is a significant hurdle nonetheless.

Perhaps a more annoying flaw of the book is its repetitiveness. While military history buffs will find the back to back case studies fascinating the casual reader could be forgiven if they quickly got bored of the same formula in each chapter of describing war after war and battle after battle and then describing how things more often than not went wrong for the perennially hapless Arab soldiers.

More amusing is that it is obvious halfway through the second chapter (regarding Iraq) not only what the main constraints on Arab military effectiveness probably are but that these will also be (and they are) the same in each country for the subsequent chapters. Chapter 3, regarding Jordan, is a bit of an exception as the Jordanian forces were generally more competent than their peers, but in the end Pollack reminds us that Jordanian’s better performance was ultimately not decisively better vs. the Arab average.

Frankly some readers will get so tired of the Arabs being beaten again and again that they will begin cheering for them to beat the more qualified Israelis and Americans at least once. There is something inherently perverse of wanting to see illegitimate, backwards and non-democratically regimes triumphing in wars that more often than not they provoked, or started for reasons of grandeur and vanity, instead of self-defence or legitimate grievances. No one likes America or Israel more than myself but at certain points in reading the book even I wanted the Arabs to win an outstanding victory and humiliate their enemies. Surely this is not what Mr. Pollack had in mind when he wrote this book.

One personal pet peeve I have is Pollack’s portrayal of General Sa’d ad-Din Shazli, the Chief of Staff of the Egyptian armed forces during the 1973 war. Whereas most Western and Arab accounts of the war generally credit him as one of the key architects of the planning and execution of Egypt’s war effort that nearly defeated Israel Pollack diminishes him ruthlessly. Instead of being one of the few Egyptian generals who acquitted himself well in 1967 he apparently was among the first to run. Instead of being a good strategist and a methodical planner he was actually picked to be Chief of Staff due to his charisma. Instead of opposing Sadat’s I’ll-fated offensive into the Sinai in 1973 he supposedly endorsed it. While I would never suggest that after having read a few dozen books on Middle Eastern Military History that I am in a better position to make a judgement on a key commander during one of the conflicts versus an ex-CIA analyst such as Pollack it is confusing that that his is the only book, indeed the only source, I have read that has questioned General Shazli’s competency.

Yet all of these flaws are minor compared to the considerable strengths of the book. Ultimately his main arguments are unchallengeable, his criteria and minute details are exhaustingly thorough and his case studies are both simple and illuminating. This work, along with Michael Oren’s “Six Days of War,” are arguably among the top 5 most important books on modern Middle Eastern conflicts to be written in the last 15 years.

“Arabs at War” is vital towards understanding the armed forces of the Arab nations in the Middle East. It proves, almost singlehandedly, that for all the significant numbers and quality of their soldiers, equipment and weapons platforms, for all the money and effort spent on training and maintaining their armies, and even with the almost unparalleled experience these forces have had in warfare, that in the end the Arab conventional military threat towards America, the West, Israel, and often even among themselves, is ultimately small and negligible. As Mao would say, Arab armies are like a “paper tiger.”

One can only imagine how different things could have been if they had decided to invest in education, healthcare, social programs and stable, inclusive and democratic institutions instead of waging pointless and debilitating wars that inevitable ended in defeat. After “World War 2” several former colonial possessions in the Far East, later nicknamed the “Four Asian Tigers,” did this and in 2 generations generally caught up to the West in regards to democracy, economic prosperity and standard of living instead of relying on incessant warfare and unnecessary confrontation. It is obvious which method of statecraft is superior.